The Original Frontier

We stand today on the edge of a New Frontier—the frontier of the 1960s—a frontier of unknown opportunities and perils—a frontier of unfulfilled hopes and threats. . . . Beyond that frontier are the uncharted areas of science and space, unsolved problems of peace and war, unconquered pockets of ignorance and prejudice, unanswered questions of poverty and surplus. . . . I am asking each of you to be pioneers on that New Frontier.

--John Fitzgerald Kennedy

Speaking these eloquent words on July 15, 1960, John Fitzgerald Kennedy accepted the Democratic Party’s nomination for President and set the tone of his coming administration in terms he would return to repeatedly. In his use of words like frontier and pioneers, Kennedy’s rhetoric was saturated with the idiom of the American West, particularly appropriate when he was looking forward to his cherished space program and specifically the race against the Soviets to land a man on the moon. But the concept of the New Frontier extended to every aspect of Kennedy’s presidency. His foreign policy centered on the issue of frontiers. As an ardent Cold Warrior, he viewed the United States as locked in a life-and-death struggle with Communism, which he pictured as a barbaric enemy pressing everywhere upon the borders of the Free World, much the way the Indians were envisioned as impinging upon the frontiers of civilization in the Old West. In his nomination speech, Kennedy shows an acute awareness of frontiers: “Communist influence has penetrated further into Asia, stood astride the Middle East and now festers some ninety miles off the coast of Florida.” In Kennedy’s domestic policy, the New Frontier took the form of a fight against prejudice, chiefly in his support of the civil rights movement, and also a fight against poverty.

New Frontier Heroes

In offering himself as a New Frontier hero, Kennedy genuinely looked the part, almost as if he had come straight out of Hollywood central casting. His public image was pure Western—a combination of good looks, masculinity, youthful vigor, and strong leadership. Like a typical hero out of the Old West, he claimed to stand for justice, freedom, and concern for common people. But Kennedy’s resemblance to a Western hero had its problematic aspects, which point to the tensions and contradictions in his presidency and the brand of liberalism he represented, what has been called “Kennedy liberalism.” The typical Western hero of Hollywood and other forms of American pop culture is celebrated as a peacemaker, and yet he often seems trigger happy, a bit too eager to reach for his gun to solve all problems. The heroic gunfighter often leaves a trail of death and destruction in his wake. Similarly, Kennedy positioned himself as a man of peace—after all, he founded the Peace Corps—but in his aggressive confrontations with Communism, he brought the world to the brink of nuclear war in the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962, and, in Southeast Asia, he pursued policies that eventually left the United States mired in the Vietnam War.

The Western hero is the champion of the weak against the powerful—the poor farmer against the cattle baron, for example—and yet he often plays the role of strong man himself to accomplish this task. He tends to set himself above common people in the very act of protecting them, claiming for himself extraordinary powers and the right to determine singlehandedly what is good for the masses. Similarly, Kennedy championed freedom, particularly in contrasting the United States with the totalitarianism of big government in the Soviet Union, but in his economic and social policies at home, he often seemed to support big government himself. In issues such as civil rights, he seemed to think that only expanding the power of the federal government could secure the freedom of American citizens. His active domestic policy thus became the counterpart of his active foreign policy. He viewed government, especially in the person of a vigorous executive, as necessary to protect people against any kind of oppression, foreign or domestic. Kennedy liberalism thus presents a paradoxical mix—a foreign policy of peace combined with aggressive anti-communism on all fronts, a celebration of freedom combined with a call for a more active executive and hence an expansion of the power of the presidency and government in general. These are precisely the paradoxes of the American Western. Its hero is often a strong man protecting the weak, shooting up bad guys in the name of peace, and constantly stretching the power of the law in the name of upholding it.

If John Fitzgerald Kennedy mirrored the American image of the Western hero, his image was in turn mirrored in the popular culture of the 1960s in an iconic figure with a similar sounding name—James Tiberius Kirk (William Shatner) of the television series Star Trek (1966-69). As captain of the starship Enterprise, Kirk pursues a “foreign policy” remarkably similar to Kennedy’s. He too is a Cold Warrior, determined to advance the cause of freedom throughout the galaxy. He is always working to thwart incursions by the totalitarian Klingons or Romulans into the space territories under the authority of the galactic equivalent of the United States, the United Federation of Planets.[1] Although Kirk constantly praises the virtues of diplomacy and the peaceful co-existence it can achieve and maintain, he is always ready to reach for his phaser or his photon torpedoes to deal with alien threats. At times he easily outdoes JFK—he brings, not just the earth, but the whole galaxy and possibly the entire universe to the brink of destruction.

Kirk also pursues an active “domestic policy” in the galaxy, following Kennedy in championing the oppressed and downtrodden, and seeking to put an end to prejudice, ignorance, and poverty wherever he finds them. But his concern for the weak frequently leads Kirk to adopt the pose of the strong man, sometimes becoming virtually indistinguishable from the tyrants he opposes. Despite Star Trek’s famous Prime Directive, which dictates a policy of non-intervention on the part of a Federation starship in the development of alien peoples, Kirk repeatedly interferes in the life of the planets he visits, sometimes remaking alien civilizations from the ground up. Kirk’s goal is always admirable: to free a people from bondage to superstition, religious idolatry, or some other form of ignorance and prejudice that enslaves them. But despite insistent rhetoric to the contrary, he characteristically views the civilizations he encounters around the galaxy as primitive, backward, and incapable of the self-development mandated by the Federation. He rarely hesitates to substitute his own enlightened vision for local beliefs—and does so more or less singlehandedly and on his own initiative—all in the name of spreading freedom and democracy throughout the galaxy, in opposition to the totalitarian regimes represented by the Klingons and the Romulans.

As a result, Star Trek offers a vision of the future in which an intellectual and specifically a scientific elite will heroically bring the benefits of technology and the liberal idea of freedom and democracy to backward peoples all around the galaxy—whether they happen to want these benefits or not. Accordingly, Captain Kirk is always paired with his Science Officer, the brainy Mr. Spock (Leonard Nimoy), just as Kennedy was always linked to his Harvard brain trust, the likes of McGeorge Bundy, John Kenneth Galbraith, and Robert McNamara. Star Trek helps highlight the tension at the heart of Kennedy liberalism, the uneasy alliance between a democratic, egalitarian spirit and a strong streak of intellectual elitism. As in the Kennedy Administration, in Star Trek common people suffering from prejudice and oppression are the chief object of concern, but their liberation—and hence their destiny—rest in the hands of very uncommon leaders. Their various forms of expertise are necessary to save the day, thus elevating the intellectual elite to heroic, almost aristocratic status. That may explain why one of the most democratic administrations in American history is remembered today by the strangely aristocratic-sounding name of “Camelot.”

Given all these parallels, it comes as no surprise to discover that Star Trek, like the Kennedy Administration, routinely harked back to the American West. Viewers tuning into the show week after week were first greeted by the voice of Captain Kirk solemnly intoning the keynote of the series: “Space—the final frontier.” The creator of Star Trek, Gene Roddenberry, said that he sold the concept to the NBC network as “Wagon Train to the stars,” packaging it as the science fiction equivalent of a TV Western very popular at the time.[2] One might at first be tempted to think that, given the timing, Star Trek derived its idea of space as the final frontier from JFK’s New Frontier.[3] But, in fact, Star Trek had direct roots in an American Western that predated Kennedy’s New Frontier by several years. Although Gene Roddenberry is today virtually identified with Star Trek, before the series he had a significant career as a television writer dating back as early as 1954.[4] Roddenberry made a major contribution as a writer to one of the most successful of all TV Westerns, Have Gun-Will Travel, which ran on CBS from 1957 to 1963 and was consistently among the highest rated programs on television. It is the fifth-longest running Western in TV history.[5] In the show’s six seasons, out of a total of 225 episodes, Roddenberry is credited as the writer of 24 of them. Viewing these episodes today, one cannot help being struck by how many of the ideas and motifs of Star Trek had their origin in the earlier Western. If space came to be the final frontier for Roddenberry--an inspired vision of the distant future--the original frontier for him was in U.S. terms the oldest frontier of them all, the American West.

Studying Have Gun-Will Travel can help us better understand Star Trek, as well as the Kennedy brand of liberalism that Roddenberry embraced and portrayed in both series. And the story of his involvement in Have Gun can change our view of the nature and history of both the Western and television more generally. It becomes a significant case study in the collaborative nature of television creativity and also a challenge to our assumptions about the sharp boundaries between different genres in popular culture. Finally, the many thematic connections between Have Gun and Star Trek call into question the common belief that the Western is by nature a politically conservative genre. If we can find anticipations of Kennedy liberalism in a TV Western that began in 1957, we must revise our picture of the history of pop culture. Liberal revision of the Western did not begin in the movies of the late 1960s, as is generally assumed, but was already flourishing in the heyday of supposedly simplistic shoot ’em up horse operas on television in the 1950s.

Fast Gun for Hire

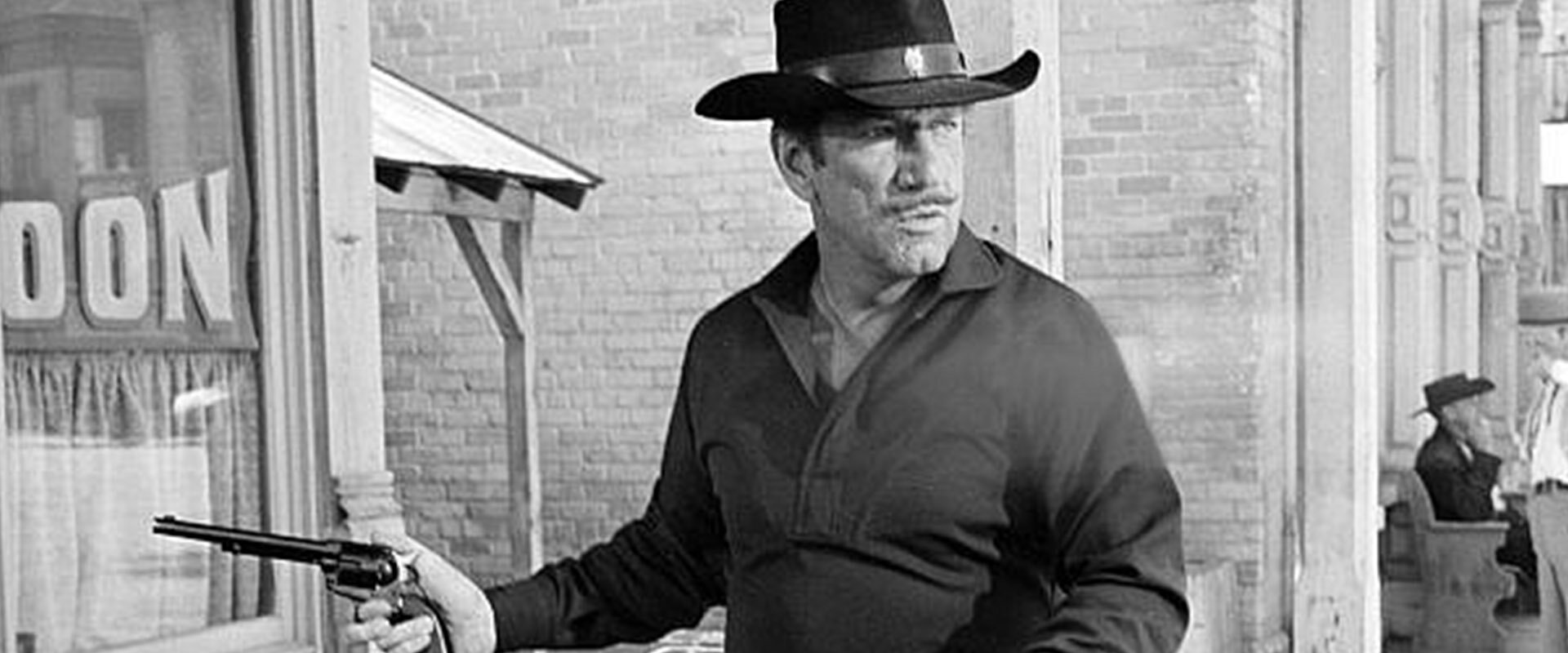

Have Gun-Will Travel was from the beginning regarded as the thinking man’s Western.[6] Created by Herb Meadow and Sam Rolfe at the height of television’s love affair with the genre, it was the most intelligent, sophisticated, and cultured of the classic TV Westerns, unrivaled in the quality of its writing until David Milch brought his series Deadwood to HBO in 2004. The hero of Have Gun is a man called simply Paladin (Richard Boone), “a knight without armor in a savage land,” according to the show’s memorable theme song. His very name conjures up images out of chivalric romance and hence the aristocratic and distant past.[7] He is a professional gunman, who sells his services to solve a wide variety of problems and disputes, in cases where the use of force is likely to be necessary. Back in his home base of San Francisco, and financed by his gunfighting income, Paladin leads the life of a cultivated gentleman, a combination of patron of the arts, gourmet, bon vivant, and playboy. But out on a job, Paladin is all business, one of the fastest draws in the West, with the military knowledge of a West Point graduate and the tracking ability of Indians (among whom he has lived and learned their languages and customs). Paladin is so versatile that in one episode he can trade blows with the British bare knuckle boxing champion (“The Prize-Fight Story” [#30]), while in another he can trade witticisms with Oscar Wilde during his lecture tour of the West (“The Ballad of Oscar Wilde” [#51]).[8] Although he is always prepared to kill in cold blood, Paladin also is capable of mercy and remorse. In an era of largely one-dimensional heroes in TV Westerns, Paladin stood out by virtue of the complexity of his character.[9]

Paladin is such a complex figure that in Star Trek terms, he can be viewed as a combination of Captain Kirk and Mr. Spock. Like Kirk, Paladin claims to be a man of peace, and always tries to use diplomatic means to settle disputes and to avoid bloodshed if possible. But also like Kirk, Paladin has a proud and aggressive nature. He has a highly developed sense of honor and of his own dignity. He is quick to take affront at any challenge to his honor; he has a short temper; and he frowns upon any attempt to question his integrity and authority. Although he is disposed to keep out of a fight, once he gets into one, he is implacable in trying to win it. In short, like Kirk, Paladin perfectly embodies the paradox of the warlike man of peace. Sharing a kind of hypermasculinity with Kirk, Paladin also resembles him in his proclivity for womanizing.[10] Both heroes leave a trail of broken hearts wherever they go. Females of all types (of all species in Kirk’s case) fall in love with the two as manly and exotic strangers, but unfortunately for these women, both Paladin and Kirk appear to live by the principle of “love ’em and leave ’em.”

But for all these aggressive and erotic impulses, in many respects Paladin more closely resembles Spock.[11] He prides himself on governing his life by logic. He is extremely intelligent and learned, prizing reason above all other human attributes. Again like Spock, Paladin is often called upon to solve mysteries by the process of rational deduction. He is a champion of enlightenment, using reason to cut through the fog of superstition and prejudice. Paladin hates ignorance and groupthink. The mindless lynch mob is his greatest (and recurrent) enemy. Like Spock, Paladin often expresses a kind of aristocratic contempt for the average run of human beings who fail to live up to his high standards of rationality.[12] The intellectual elitism of the figure links him to what we have seen in both the Kennedy Administration and Star Trek. In his uncommon and highly cultivated nature, Paladin looks forward to another Star Trek hero, Captain Jean-Luc Picard. He was Kirk’s replacement as the commander of the Enterprise in The Next Generation (1987-94), Roddenberry’s second go at a Star Trek TV series. Like Picard, Paladin is strangely bookish for an action hero. He likes to quote classical sources (Cicero in the original Latin in “The Golden Toad” [#88]), and words from Shakespeare as well as Romantic and Victorian poets flow from his lips. All this intelligence, rationality, learning, and highly developed taste for the classics of European culture heighten in Paladin the traditional paradox of the Western hero: he is an aristocratic figure serving democratic ends.[13]

Paladin resembles later Roddenberry heroes like Kirk, Spock, and Picard so closely that we must remind ourselves that he did not create the central figure of Have Gun-Will Travel himself. Paladin was the brainchild of Meadow and Rolfe, and the character had taken its essential form before Roddenberry began writing for the series. Although Roddenberry wrote what are widely regarded as some of the best episodes of the show, his contributions as a writer were by no means unique, in either quality or the direction in which he develops the character of Paladin. For example, Roddenberry frequently has Paladin quote Shakespeare, but so do several of the other writers, and the most Shakespearean of all the episodes, a recreation of Othello called “The Moor’s Revenge” (#54), was written not by Roddenberry but by Melvin Levy.[14] What is really interesting about Have Gun for students of Star Trek is to see Roddenberry developing ideas for the later series precisely while working within a formula originally established by Meadow and Rolfe. An important lesson in the collaborative nature of TV creativity can be learned from observing what are often viewed as the unique ideas of Star Trek incubating in an earlier series created by writers other than Roddenberry.

In its broad outlines, the formula for a typical Have Gun episode is very close to the Star Trek formula. Just as the Enterprise lands on an alien planet, Paladin typically rides into a Western community as a stranger in a strange land. The local inhabitants seem alien to him, and he seems alien to them. Dressed all in black, he stands out in a crowd in an ominous way, almost, one might say, as if he had come from another planet. The locals typically distrust him as an outsider and are particularly suspicious of him because he fits their stereotype of an evil gunfighter, and they do not like a stranger interfering in their affairs. At the same time, the customs and conditions of the community are opaque to Paladin. Either the real power structure of the community is concealed, or some dark event in the past governs the present, or perhaps just the odd behavior of the inhabitants blinds Paladin to what is truly going on. Like the crew of the Enterprise, Paladin is challenged with uncovering the mysterious forces that rule the community into which he has wandered, and thus breaking the impasse into which it has backed itself, or otherwise solving its problems, often to save his own life or at least to free himself from some form of imprisonment. Combining the talents of Kirk and Spock, Paladin must demonstrate his superiority by proving his adaptability to local conditions.

Paladin’s great virtue is thus his cosmopolitanism. Like the crew of the Enterprise, he has traveled extensively and learned to size up an alien situation quickly. He does not possess the Enterprise’s convenient Universal Translator, but his command of languages is exceptional for his day. He knows a little Chinese, speaks several Indian languages, and in general has great skill at communicating with people apparently foreign to him. One of the keys to his repeated success is his tolerance. His wide travels have taught him an appreciation of and sympathy for different customs and ways of life. He therefore does not let prejudices stand in the way of his understanding and dealing with an unfamiliar situation.

Roddenberry himself recognized the parallels between Have Gun and Star Trek when he was trying to sell another science fiction series to NBC and argued that the success of the Western augured well for his new project:

Assignment: Earth could also be called Have Gun-Will Travel 1968! Yes, I’m quite serious, and should know what I’m talking about. As well as being co-creator of Assignment: Earth I also was head writer of Have Gun-Will Travel. The prime dramatic ingredients of the two shows are almost identical—both shows feature a slightly larger-than-life main character, who sallies forth weekly from a familiar “home base” to do battle with extraordinary evil in an action-adventure format. As top HG-WT writers were aware . . . , there were a surprising number of “science fiction” ingredients in the character of Paladin. Certainly for a person living in 1872, his remarkable knowledge, attitudes and abilities were very much that of a man from “another place” or “another time.” In fact, one of Paladin’s most effective dramatic tools and charms was his detached and superior, sometimes almost condescending, perspective from which he viewed the fallible world about him.[15]

Roddenberry is shrewdly peddling his wares to NBC here, but he still displays keen insights into the character of Paladin and the nature of Have Gun in general, and reveals that he thought of himself as in some sense already writing “science fiction” when he was working on the earlier Western.

The structural parallels between Have Gun and Star Trek point to the key thematic similarity between the two series—celebrating toleration as the central and universal virtue. When Roddenberry was concerned that Paramount’s Star Trek films were deviating from his original conception, he tried to get the franchise back on course by writing a long letter to the producer who had replaced him in the film series, Harve Bennett. He stated very clearly what he regarded as the fundamental principle of the Star Trek universe (and as its creator, he was convinced that he ought to know):[16] “to be different does not mean something is ugly or to think differently does not mean that someone is necessarily wrong.”[17] These words could serve equally well as the motto of the typical Have Gun-Will Travel episode. Like the crew of the Enterprise, Paladin repeatedly finds himself caught between warring factions or tribes or ethnic groups, forced to negotiate their differences, and to show that, for all their obvious oppositions and divisions, deep-down they have something in common, which can provide the basis for their living together in peace and prosperity.

Learning to live with difference is thus the central theme that unites Have Gun with Star Trek. Both series constantly teach the need to overcome prejudice, especially hateful and harmful stereotypes. Sam Rolfe took pride in this aspect of his series:

We couldn’t have an actor, say, come out and tell a whole town that they’re prejudice[d] toward religion or ethnics. But we were able to tell the same story without using those words—such as prejudice, and viewers kept tuning in each week not because they liked the fiction, but because they knew it was true. . . . They couldn’t admit that prejudice was next door, but could accept a drama that was.[18]

To be sure, both series often fell into the trap of perpetuating stereotypes even while seeking to combat them. Although both could lay claim to feminist credentials in seeking to provide positive images of powerful women, particularly in positions of authority traditionally reserved for men, they also often presented women in demeaning stereotypes, partially as a result of Paladin’s and Kirk’s incorrigible womanizing, and also because of a tendency to exoticize female characters, often as irrational and incapable of living up to masculine standards of discipline.[19] The record of both series in portraying race is also equivocal. In Have Gun, the role of Hey Boy (Kam Tong), a porter in Paladin’s hotel who is effectively his servant, is an example of orientalist stereotyping. As his name indicates, Hey Boy is infantilized and placed in a subordinate position. He is frequently portrayed as superstitious and often embodies the stereotype of the Inscrutable East. But a number of episodes give Hey Boy a more active role and are clearly meant to emphasize Paladin’s respect for Chinese culture in all its ancient wisdom.[20] Similarly, Paladin is repeatedly shown to be a friend of the Indians, and he often defends their interests while displaying a genuine knowledge of their culture.[21] And yet by contemporary standards, Have Gun is painfully stereotypical in its portrayal of what we now call Native Americans, sometimes presenting them as little better than ignorant and cruel savages.[22]

Much the same can be said of the treatment of race in Star Trek. Roddenberry prided himself on offering a multicultural, multiracial view of the future, and the show became famous for presenting the first interracial kiss—between Kirk and Lt. Uhuru (Nichelle Nichols)—on prime time network television.[23] And yet, as many commentators have pointed out, the command structure of the Enterprise, and of the United Federation of Planets more generally, remained predominantly white. Racially darker figures like the Klingons and the Romulans tended to be presented in a negative light. There can be no question that both Have Gun-Will Travel and Star Trek fail to meet contemporary standards of political correctness.[24] But it is important to remember that by the standards of their own day, both shows were progressive on issues of race and gender—and were deliberately intended to be so. Thus, in analyzing Roddenberry’s apprenticeship in Have Gun-Will Travel for ultimately creating Star Trek, one is primarily looking at how he learned to write effective parables of the need for toleration and of the appreciation of what is today called diversity.

The Armenian Helen of Troy

Of all the stories Roddenberry wrote for Have Gun-Will Travel, perhaps the one most clearly linked to Star Trek is a first-season episode called “Helen of Abajinian” (#16).[25] The title is clearly intended to recall Helen of Troy, as is the name of a third-season episode of Star Trek, “Elaan of Troyis” (#57). The exotic dance performed by the eponymous heroine of “Helen of Abajinian” is very similar to one in the pilot of Star Trek, “The Cage” (#1). If one were looking for Roddenberry’s personal obsessions in Have Gun and Star Trek, his fascination with the Helen of Troy archetype would be a good place to start. Roddenberry seems to have been fixated on stories about beautiful, exotic women, who are the source of conflict among aggressive males, driving them to distraction, if not destruction.[26] One way in which Paladin proves to be a forerunner of Captain Kirk is that he must learn how to use the female of the species to bring peace rather than war to men, and to do that, he must learn to channel the sexual power of women for constructive purposes. That perhaps explains why some of Roddenberry’s most persistent fantasies seem to have involved the domestication of a Helen of Troy figure.[27]

In “Helen of Abajinian,” a wealthy winemaker named Sam Abajinian (Harold J. Stone) has hired Paladin to rescue his daughter Helen (Lisa Gaye), whom he thinks has been abducted by a young cattle rancher named Jimmy O’Riley (Wright King). In the Roddenberry universe, it turns out that the man rather than the woman is the victim. Helen has run off with O’Riley in a scheme to lure him into marriage. In a typically conflicted situation, Paladin must mediate among a whole series of opposing forces. He must get O’Riley to want to marry Helen, and at the same time reconcile Abajinian to having Jimmy as a son-in-law and Jimmy to having Sam as a father-in-law. Paladin’s task is complicated by a whole set of ethnic and other differences that cut across the battles between the sexes and between the generations. As a grape grower, Sam has a farmer’s mentality and Jimmy is locked into the way of thinking of a cattle rancher. As a result, they quarrel over questions of land use in a fashion typical of the Western. Moreover, Jimmy is presented as a straight-laced, mainstream American, whereas Abajinian is a colorful Armenian immigrant, speaking with a heavy foreign accent, and accompanied by a couple of ethnic sidekicks named Gourken (Vladimir Sokoloff) and Jorgi (Nick Dennis). Sam has all sorts of Old World notions, including an extreme conception of honor, that make it difficult for him to deal with American customs. The episode thus tests Paladin’s cosmopolitanism, and fortunately he rises to the challenge. He can speak a little Armenian, he appreciates the fine points of Armenian cooking, and he can match and even surpass Sam when it comes to downing a potent Armenian brew. Above all, when negotiating his fee, Paladin demonstrates a complete command of Old World haggling that earns him the respect of the farmer: “My friend, you bargain like an Armenian.”

As Shakespeare’s Othello demonstrates, ethnic differences can be the stuff of tragedy, but as The Merchant of Venice shows, they can also be played for comedy. “Helen of Abajinian” illustrates how easily jokes can be generated out of the confusions and misunderstandings produced by ethnic differences. The episode even contains jokes at the expense of Kurds, which must have been truly baffling to an American audience in the 1950s. The only way Paladin can prevent ethnic conflict from leading to tragedy is to get the characters to laugh at their differences, which ultimately means getting them to laugh at themselves. His smooth cosmopolitanism facilitates that result. Have Gun-Will Travel was generally a serious show, dealing with weighty issues, but it had many humorous moments. In several of his scripts, Roddenberry displayed a particularly light touch among the writers, foreshadowing the comedy that was to liven up Star Trek. As we can see in “Helen of Abajinian,” comedy often served Roddenberry as the means of overcoming the tragic potential of ethnic difference.

Dealing with O’Riley turns out to be easier for Paladin than dealing with Sam Abajinian. After all, he has the power of Helen’s innate sexuality working for him. It is her exotic dance that finally wins the day in a scene that was to become fairly common in Star Trek (“starship crew turned on by interplanetary sexpot”). But Paladin makes sure to give a deeper significance to what might otherwise seem to be a merely sexual attraction. He displays the kind of archaeological knowledge that was to become Spock’s stock-in-trade: “Ancient Armenia was at the crossroads of the world.” Referring to Greece, Persia, and Minoa, Paladin teaches O’Riley a lesson in Roddenberry’s favorite subject, universality: “These dances, O’Riley, are a language. The most compelling, understandable, universal language of mankind.” This kind of cross-cultural communication is what Paladin has been trying to facilitate throughout the episode. O’Riley has been puzzled by the—to him—strange customs of the Armenians (“women don’t chase men”). But Paladin carefully shepherds him to the point where he makes a Roddenberryan declaration of the acceptance of difference: “Just ‘cause they don’t do things like my people, that don’t mean they ain’t real down-to-earth folks too.” By the same token, O’Riley expects some multicultural indulgence himself; when Paladin tells him that bathing before one’s wedding is an Armenian custom, the young man insists: “I’ve got my customs, too.” By the end of the episode Paladin has brought peace to all the warring parties in the valley. In a final display of his ability to bargain like an Armenian, he negotiates a generous dowry for O’Riley from the skinflint Abajinian. With Paladin’s help, the man is ready to settle down with the woman, the son-in-law with the father-in-law, and the cattle rancher with the farmer. In the terms of Star Trek, they are ready to live long and prosper.

Liberalism in the Desert

“Helen of Abajinian” was a stand-out episode of Have Gun-Will Travel and earned Roddenberry a Writer’s Guild award for the best-written TV Western script in 1957.[28] It was the kind of off-beat, change-of-pace episode that was later to characterize Star Trek at its best. A more typical Have Gun episode Roddenberry penned, the third-season “The Golden Toad” (#88), explores similar issues and also can be linked to Star Trek. Paladin once again wanders into a situation rife with divisions and tense with strife. He has come to aid a Mr. Webster (Kevin Hagen), who is in danger because he discovered an ancient Indian treasure on his property. Bitter over having been sold “no good, dried-out land” by townspeople who failed to warn him of the drought in the area, Webster is determined to keep the treasure for himself. The opposition to Webster in the town is led by a woman named Doris (Lorna Thayer), who is the big landowner in the region. Proud that her “family has owned this valley since ’32,” Doris speaks, as do many of the antagonists in the series, like a feudal aristocrat: “This is my valley—if it weren’t for me, none of you would be here.” Doris claims that she retained the mineral rights to the land she sold to Webster, and wants her share of any gold he has discovered. This is the kind of stand-off Paladin typically has to deal with—people fighting over property, mineral rights, buried treasure—and willing to kill each other for financial gain. As in an earlier episode Roddenberry wrote, “Yuma Treasure” (#14), he takes a very dim view of the obsessions generated by greed. All that Webster has actually found is a golden toad, some kind of ancient idol that the vanished Indians once worshiped, but everyone assumes that it is part of a larger treasure hoard.

Because he is free of the vice of greed, Paladin figures out what the ancient artifact really signifies. The worship of an amphibious creature like a toad must point to the presence of water somewhere in the area. By dynamiting the cave Webster has been searching, Paladin sets free an underground river that can irrigate the entire valley and end the drought. That is the true treasure of the ancient Indians—not a barren metal but the fertilizing power of nature. Having earlier solved the riddle of the golden toad, Paladin has, in fact, surreptitiously gone off to the county seat and secured the water rights to the underground river. But unlike the greedy townspeople, Paladin has no intention of exploiting anybody, and announces at the end: “In order to promote peace and increase the population in the valley, which of course will serve my interests also, additional shares will be given to each married family at no extra charge.” Paladin’s proclamation sets off a frenzy of marriages in the valley, including Doris to Webster.

Once again Paladin has saved the day and brought peace and prosperity to warring people, and he has done so by following Roddenberryan principles. Consumed by greed, the townspeople fall prey to the power of ancient myth. They believe that a buried treasure must be gold. But Paladin, with his enlightened mind, looks for a natural explanation for the ancient myth and finds it in the purely natural power of water, which ultimately will mean much more to the townspeople than any traditional treasure. Notice also the Kennedy liberalism in Paladin’s approach, a middle way between communism and capitalism. Paladin does own the water rights, but he exercises them in a civic-minded fashion, and manages to further his self-interest while aiding the townspeople. Several episodes of Have Gun-Will Travel focus on the issue of water rights, including the first one Roddenberry wrote for the series, “The Great Mojave Chase” (#3). For the liberal Roddenberry, water rights symbolize everything that can go wrong under capitalism, the ability of one individual to monopolize a resource that ought to be available to all. Roddenberry is deeply suspicious of capitalism, which he views as chiefly taking the form of robber barons.[29] His scripts for Have Gun are filled with big landowners who act like local tyrants, imposing their will on the common people who are dependent on the rich for their livelihood.

What makes Roddenberry a liberal, rather than a communist, is that he still has a limited faith in private enterprise, and does not simply offer public ownership as the solution to the problem of water rights. Like a good Kennedy liberal, he searches for a way to reconcile private ownership with public good, and offers Paladin as a model. In both “The Golden Toad” and “The Great Mojave Chase,” Paladin represents a strong and competent outside force that can intervene in a community and break up its monopolies of ownership. In both episodes Paladin behaves more like a government official than a private businessman; above all, he does not arise spontaneously from within the community but must enter it as an outsider. In the grand progessivist tradition of Teddy Roosevelt, he is a trust buster. The chief point is Paladin’s detachment from local interests and prejudices, and his consequent ability to see the big picture. Positioned above the competing local interests, he has the objectivity to come up with a solution that is beneficial to all, not just to a single individual. In this respect, Paladin foreshadows the world of Star Trek, where purely commercial interests are generally treated with contempt and the public spiritedness of quasi-governmental figures like Kirk and Spock is constantly offered as the alternative to the senseless greed of businessmen and other wealthy figures.[30]

Witch Hunt on the Frontier

“The Golden Toad” is also a prototype of a Star Trek episode in the way that Paladin finds a purely rational solution to the riddle of an ancient myth. In several Star Trek episodes, Kirk and Spock have to demystify ancient myths and they often have to solve a kind of riddle to do so.[31] This enlightenment spirit is evident in one of Roddenberry’s less successful scripts for Have Gun, the second-season “Monster of Moon Ridge” (#63), the only Halloween episode the series ever attempted. Pushing the limits of genre, Roddenberry tries to turn a Western into a horror story. Unfortunately, in the process he loses the believability that is usually the hallmark of his scripts. The episode threatens to become laughable, when we hear talk of werewolves and vampires intruding into the American frontier. The West was wild, but not that Wild. Nevertheless, the episode is very interesting from a thematic standpoint in any comparison with Star Trek. The story begins with one of the more interesting exchanges between Paladin and Hey Boy, which reflects the orientalist stereotype of the East as superstitious and the West by contrast as rational. When Hey Boy learns that Paladin is going off on a dangerous mission that may involve supernatural forces, he gives his friend what purports to be a dragon’s tooth to protect him. Paladin sets the keynote of the episode when he speaks for the Enlightenment spirit of America: “Hey Boy, your new country has a much stronger potion for driving off evil—equal parts reason and daylight.”

Paladin heads off to a remote town where rumors of a monster on Moon Ridge have left the locals on edge, their guns loaded with silver bullets. Paladin keeps laughing off the rumors and scorns the superstitions of the town. When he tells the sheriff: “Salem witch burners would be very happy in your town,” he tips us off to the deeper political significance of the episode. As is particularly evident in Arthur Miller’s famous play The Crucible (1953), throughout the 1950s the term witch hunt was a code word for McCarthyism, the overzealous pursuit of communist infiltration in government and other positions of importance in American society.[32] Hollywood was particularly sensitive to the issue of McCarthyism because of the infamous blacklisting of several writers for alleged communist sympathies. Whenever Roddenberry is dealing with superstition and the irrationality of mob psychology, he often has in mind the way anti-communist zealots like Joseph McCarthy were able to manipulate American public opinion against people with any evidence of leftwing sympathies and connections in their past.[33]

But “Monster on Moon Ridge” turns out to be a more general parable on the evils of persecution and prejudice. Paladin discovers that the monstrous apparitions on Moon Ridge have been created by a woman named Maria (Shirley O’Hara), who is trying to ward off strangers to protect her simple-minded son and the equally simple-minded daughter of a neighbor with whom he likes to play. As Paladin says, the woman feels that she has been “run out of town by ignorance and prejudice,” and now believes that she must exploit the superstitious fear of the townspeople to keep the youngsters safe from ridicule and contempt. The focus of the episode is on Paladin’s extraordinary composure in the face of the manufactured apparitions. Here he is at his most Spock-like; he behaves just as coolly as the logical Vulcan does repeatedly in similar circumstances in Star Trek. Watching the episode, I kept waiting for Paladin to say: “Fascinating,” as one spooky sight after another is paraded before him when he is chained up in a cave. Faced with what appears to be an old crone, and ever the Shakespearean, Paladin sees the theatricality of the situation: “It’s Macbeth—enter the First Witch.”[34]

Confronted by Paladin’s unflappability, Maria finally tells him: “I was afraid of you. You have no respect for witches.” In one of the show’s more feminist moments, Paladin replies: “Well, I do have respect for some things—courageous, intelligent women, for example.” As always, Paladin’s great strength is his freedom from prejudice, which translates into a freedom from superstition as well. Maria ends up celebrating the debunking power of Paladin’s Enlightenment mind: “Materialize an apparition on a broomstick in front of him and he’ll ask it to sweep the floor.” The same could be said of Mr. Spock and Captain Kirk. A number of Star Trek episodes turn on the refusal of the Enterprise crew to be taken in by ghostly apparitions and attempts to manipulate their minds.[35] This theme apparently meant a great deal to Roddenberry. In “Moon Ridge,” it prompts one of the most didactic endings in any of his Have Gun scripts. Paladin announces that the real monsters are the townspeople who would make fun of the young boy and girl simply because they are different. Despite his usual Enlightenment commitment to spreading the truth, in this case Paladin has no interest in disabusing the town of its frightening illusions: “Ignorant and prejudiced people like to be deceived and I think they deserve it when they are. Why confuse them with the truth?” This is the kind of condescension toward common people that Roddenberry himself notes in Paladin in his letter promoting his Assignment: Earth project. Perhaps something of Roddenberry’s own attitude toward his fellow human beings surfaces in the script here as well.

Indian Indians

The link between prejudice and superstition, and Roddenberry’s contempt for both, is the thematic core of another one of the change-of-pace episodes he wrote for Have Gun, the third-season “Tiger” (#89). In planning the second season, Sam Rolfe had contemplated sending Paladin off to foreign countries to extend the range of his adventures.[36] The scripts had already given him backstories that placed him formerly in exotic lands such as India and China, to which he might eventually return. But the economics of production and the fear of tampering with a successful formula were to keep Paladin squarely in the American West for the six-season run of Have Gun. But if Paladin could not go to India, perhaps India might come to him, and Roddenberry showed his versatility as a writer by supplying just the right script for the purposes. In “Tiger,” Paladin is summoned to Argus, Texas by a refugee from British India named John Ellsworth (Parley Baer). Ellsworth needs a tiger hunter and Paladin evidently was legendary as such in his earlier days in India. Ellsworth is the standard local tyrant of Have Gun scripts. He thinks that his wealth gives him the right to order anybody around, even Paladin: “I can buy and sell people like you, Mr. Gunman.” He treats the servants he has brought with him from India with disdain, and sadistically enjoys tormenting a romantic couple among them by at once encouraging and frustrating their love.

Ellsworth behaved even more abominably back in India. Pursuing his sport as a hunter, he wounded a tiger that, in its rage, went on to kill over a hundred people in Bengal. Ellsworth shows his contempt for humanity by saying off-handedly: “Maybe I am responsible for a few miserable natives dying.” By contrast, Paladin is sympathetic to the natives: “I always found the Bengalis to be a gentle people.” Ellsworth is now paying for his arrogance. He believes that he is the victim of a Bengali curse, and firmly expects that he will be killed by a tiger. He has come to Texas to get as far away as possible from India and any tiger habitat. The episode works to create something of a supernatural aura around the threat to Ellsworth, but in typical Roddenberry fashion, it ends up demystifying the curse. A tiger does show up, but it belongs to a traveling circus and is a harmless pet. Nevertheless, like Oedipus, Ellsworth runs squarely into his fate precisely by trying to avoid it. So consumed is he by superstition that merely hearing the roar of the tiger on the loose frightens Ellsworth into running off a cliff to his death. As in “Monster on Moon Ridge” and many Star Trek episodes, Roddenberry supplies a purely natural explanation for what at first appears to be a supernatural event.

What distinguishes an otherwise run-of-the-mill script in “Tiger” is the way Roddenberry has fun playing with ethnic stereotypes. Paladin can, of course, speak a little Hindi when he meets Ellsworth’s servant Pahndu (Paul Clarke), but they quickly switch to English for the following exchange when Pahndu realizes his mistake in trying to bar Paladin from access to his master:

PAHNDU: I thought you were one of the natives here.

PALADIN: Natives? Oh yes, a quaint lot.

PAHNDU: Very strange, and I’m afraid dangerous.

PALADIN: Only when restless.

Here white Americans are subjected to the prejudices normally invoked in scripts about Indians or other exotic foreigners. Roddenberry is enjoying reversing perspectives and standing stereotypes on their head, something Star Trek does all the time. “The natives are restless” is a cliché of jungle adventure stories, typically spoken by white explorers of the Africans or Asians or South Americans they are hunting down or otherwise trying to exploit. Here the Easterner Pahndu turns the tables on the Westerner Paladin, who plays along with the game. As a civilized Indian having come to the wilds of Texas, Pahndu looks on Americans as the dangerous natives for a change. Moreover, he finds American customs quaint and puzzling. He asks Paladin about a strange rite he refers to as a “box dance.” It takes even the quick-witted Paladin a moment before he realizes that Pahndu is asking him about that most American of customs, the square dance.

In a reversal of orientalist disparaging of the East, Pahndu reacts to news that a Texas mountain lion is too small to be mistaken for a tiger: “Even in animals, this is an inferior continent.” Roddenberry also plays with the ambiguity of the word Indian in the episode. The townspeople refer to Pahndu as “Ellsworth’s Injun” and challenge him: “Tell us again what tribe you’re from.” By the time Roddenberry is through ringing the changes on ethnic stereotypes, we come away from “Tiger,” not agreeing with Rudyard Kipling that “East is East, and West is West, and never the twain shall meet,” but rather wondering how to keep East and West clearly distinct in our minds if an Indian can be an Injun and Paladin a restless native. By shifting us back and forth between Eastern perspectives on the West and Western perspectives on the East, Roddenberry uses “Tiger” to teach a lesson in cultural relativism. The multicultural perspectivism of the episode is a harbinger of many Star Trek scripts to come.

How to Handle a Lynch Mob

“Tiger” is a story of prejudice appropriately punished by superstition. The very close-mindedness in Ellsworth that leads him to treat the Bengalis with contempt makes him susceptible to believing that they have the power to put a curse on him. In writing for Have Gun-Will Travel, Roddenberry was already focusing on the dangers of close-mindedness, especially insofar as it manifests itself in forms of groupthink like superstitious beliefs. We have already seen him critical of the witch hunt mentality; a related theme basic to the Western is the lynch mob. Many episodes of Have Gun take up this theme, including several of Roddenberry’s scripts.[37] The best of these is “Posse” (#82) in the third season. The plot is familiar, but Roddenberry gives it a novel twist. Wandering as usual, Paladin comes upon a seemingly pitiful and helpless saddle tramp and makes camp with him. But Dobie (Perry Cook) is, in fact, a murderer and has come up with a clever plan to shift his guilt onto Paladin when they are both found by the posse that has been hunting for the tramp. While Paladin is not paying attention, Dobie make things look as if Paladin has overpowered him and even succeeds in planting the murder weapon in Paladin’s saddle bags.

The story generates the powerful dramatic tension that always comes from watching an innocent man on trial for his life in illegal and unjust proceedings. Paladin has to use all his considerable wits to escape the attempt to hang him, and only a slip of the tongue by Dobie reveals his guilt and exonerates Paladin. The episode explores all the issues a lynching usually raises in Westerns, the whole problematic of people taking the law into their own hands.[38] Once again the story features a local tyrant—a cattle baron named McKay (Denver Pyle)—who flaunts his power by dominating the deliberations of the posse and overruling the sheriff whenever he wants.

But Roddenberry puts the emphasis on an unusual aspect of the situation—Paladin’s heroic refusal to be rattled by the danger of his circumstances. For Roddenberry the episode becomes a case study of how to deal with the psychology of a lynch mob. Paladin again plays a Spock-like role, keeping cool in circumstances that would drive most people to fall apart emotionally.[39] In response to any provocation, he maintains his rationality and is determined to stand or fall with the power of logic. When the sheriff questions his behavior: “An innocent man would be begging now, mister,” Paladin logically replies: “So would a guilty one.” In Paladin’s analysis, the real danger he faces is the irrationality of mob behavior. By refusing to beg for his life, he is pursuing a deliberate strategy: “I’d rather give this gathering a chance to do some thinking.” That is why he will not give the mob the emotional display it craves: “A good lynching needs tears and screams and terror--the more excitement, the less thinking.” Paladin is an astute analyst of lynch mob psychology, and understands that it depends on a process of scapegoating and victimization: “The ideal victim is mentally or emotionally ill. . . . Lynchers have to be content with people that are merely a little bit different—little people, the weaker they are, the better.”[40]

Roddenberry thus returns to his central goal of defending the right to be different. He condemns mobs because they constitute their identity by defining themselves in opposition to a lone victim who is somehow different. They are like a pack of animals ganging up on the weakest member of the group and killing it. Thus Paladin must be at his strongest in this episode. Any sign of weakness on his part and the pack will turn on him. He is, in fact, at his most aggressive and sarcastic in “Posse.” In circumstances in which most people would feel compelled to humble themselves and beg for mercy, Paladin bristles with pride and speaks with utter contempt for the men who hold his life in their hands. When the posse finally realizes their mistake, they go ahead and lynch Dobie anyway, thus confirming Paladin’s contempt for them as a mob. His last words in the episode are “Heaven help us from what men do in the name of good.” Paladin is a strange kind of American hero. Although he usually stands up for the rights of common people, he does so from an aristocratic perspective, which often involves contempt for their judgment, especially when it manifests itself in any form of groupthink. The more “common” the thinking, the more Paladin despises it. For Roddenberry, the problem seems to be that common people, mired in their commonality, will not allow individuals to be different.

Roddenberry thus crafts a distinctive take on the standard Western lynch mob plot. Ordinarily in such a story, Dobie would have been saved at the end, at least for a fair hearing in a courtroom. The posse would have learned the errors of their ways and balked at trying to lynch two men in one day. Frequently the leader of the lynch mob would have been discredited, perhaps by having been revealed to be evil in some way, with an ulterior motive for lynching the particular victim. But, although McKay has some elements of the typical wealthy villain in Have Gun, Roddenberry insists on making him a semi-sympathetic character. He gives McKay a long speech eloquently defending the need to resort to vigilante justice. In words that resonate with a brand of Western rhetoric that we just saw in Ford’s The Searchers (1956), McKay talks of how difficult it was to create civilization on the frontier. He goes on to say: “It wasn’t the law that done that. A lot of hard work, sweat, a few guns, a couple of ropes.” McKay thus explains why they are taking the law into their own hands: “That’s why we got more faith in trees than courthouses.” Roddenberry does not want McKay to come across as an evil man. Recall that Paladin insists: “Heaven help us from what men do in the name of good.” He does not question the sincerity of McKay or his fellow vigilantes. That makes his critique of groupthink all the more powerful. The recurrent witch hunts and lynch mobs in Roddenberry’s scripts point to the problem with common people—when they think in common, they automatically assume that what they are doing is for the common good, and thus they may end up doing evil in the name of good. In his scripts Roddenberry frequently juxtaposes a brave individual who is right against a crowd that finds strength in numbers and blunders into wrong. This is a motif Roddenberry was later to develop in many Star Trek episodes.

The Night Before Christmas

A story that epitomizes the foreshadowing of Star Trek in Have Gun-Will Travel is “The Hanging Cross” (#15), an only partially successful attempt at a Christmas episode in the first season (it was first broadcast on December 21, 1957). The story is vaguely reminiscent of The Searchers; it deals with the attempt to recover a white child who has been stolen by Indians. Paladin is working for a rancher named Nathaniel Beecher (Edward Binns), yet another of the unending sequence of tyrannical rich men in Have Gun (Paladin appears to be the only human being uncorrupted by money in the series, perhaps because he uses it to enjoy himself, not to exercise power). Beecher throws his weight around in the community by throwing his money around. At a key moment in the plot, he gets his ranch hands to follow his lead by threatening to fire them all. Sounding like a frontier Bertolt Brecht, Beecher cynically says of his economic control over his hands: “The belly always wins out.” The great grief of Beecher’s life is that his son Robbie (Johnny Crawford) was kidnapped when very young by the Sioux. As the story opens, Beecher has located a boy he believes to be his long-lost son among a traveling band of Pawnees and has taken him against his will back to the ranch. Naturally Paladin speaks Pawnee and can serve as Beecher’s interpreter in talking to the boy, who is extremely uncomfortable in his new and unfamiliar surroundings.

The episode becomes yet another study of Paladin mediating between different ethnic groups, in this case the classic Western opposition between the cowboys and the Indians. Beecher speaks contemptuously of Paladin as an “Indian lover,” but it turns out to be fortunate that he is, because only his closeness to the Indians allows him to negotiate with the Pawnees once they steal the boy back. To the Pawnees, Paladin is known as “he who rides with many tribes,” and they trust him. Paladin is once more cast as the cosmopolitan man who is uniquely qualified to bridge the gap of cultural difference.

Roddenberry evidently took his task of writing a Christmas episode seriously. “The Hanging Cross” is one episode in which Paladin voluntarily hangs up his gun and refuses to use it to solve the problems he is dealing with. On Christmas Eve, he truly becomes a man of peace. At a Christmas celebration, he gives a long speech in praise of peace that is a model of the sort of wordy oration Captain Kirk is given to in Star Trek. Beecher plays the role of Scrooge in the Christmas scenes. Although he does not quite get around to saying: “Bah, humbug!”, he does complain about having to listen to “preachin’ from a gunslinger.” Despite Paladin’s heroic pacification efforts, the episode appears to be building up to a bloody climax. Beecher and his hands come to the Pawnee camp itching to recapture the boy and to punish the Indians, in particular to hang their chief. But at the last minute, not the U.S. cavalry but the remaining townspeople come to the rescue. Led by women and children, they interrupt the violent confrontation that is developing and spread Christmas cheer among the heathen, carrying baskets full of holiday food. Under the circumstances, even Beecher cannot bring himself to commit violence, and as a reward for his forbearance, he receives proof in the form of a ring that the boy really is his son. If we have not yet figured out that we are watching a Christmas episode, in the final moments, the gallows Beecher has had erected casts the shadow of what is clearly a cross in Paladin’s path. It is unusual, to say the least, to see such a conventionally Christian symbol in a Roddenberry script. But it is, after all, Christmas.

Roddenberry even has Paladin take a stab at explaining Christmas to the Pawnees, reassuring them that this is the one night of the year when the white people honor their children and thus can be trusted. As usual, Paladin brings peace and hope to people for whom war and despair had seemed to be looming. He displays a genuine sympathy for the plight of the Pawnees and is prepared to take their side in the conflict. And yet the Pawnees pay a great price for the solution Paladin comes up with to their problems. They must surrender the boy, not just physically but culturally. He had been stubbornly refusing to speak anything but Pawnee, but by the end of the episode he seems proud to have learned how to say “Christmas.” As we saw Paladin do with Sam Abajinian, he uses the leverage he has gained with Beecher to negotiate a good deal for the Pawnees, getting them 500 acres of Beecher’s land. But in order to settle on this land, the Pawnees are obviously going to have to abandon their traditional nomadic way of life, specifically their warrior ways. The 500 acre grant smacks a little too much of a reservation. There is something paternalistic about Paladin’s solution to the Indians’ problems. He is playing the traditional role of the Great White Father.

The Intellectual as Superhero

“The Hanging Tree” thus highlights the tensions at the heart of Have Gun-Will Travel. As we have repeatedly seen, Paladin heroically fights for the common good, but he typically expects to be the sole person to dictate the precise terms in which it will be formulated. He enters a different world each week as a stranger, and uses his outsider status to assess objectively what is wrong with it. The local inhabitants are incapable of doing so on their own by virtue of their belonging there and thus being captive of a certain set of traditions, prejudices, and closed horizons. Paladin typically ends up remaking the communities he visits, with the welfare of the inhabitants in mind and guided by liberal democratic principles. Nevertheless, in the name of freedom and democracy, he usually sets himself up as superior to the community he is helping, imposing his own solution on it and often expressing open contempt for the people who run it and the way it understands its own interests. In all his travels, Paladin never seems to come upon a functioning community, with a set of decent political institutions that make it capable of self-government.[41] The local authorities he deals with are almost always corrupt, or too weak to handle a crisis. The premise of Have Gun seems to be that ordinary human beings left to themselves will destroy each other in senseless conflicts, chiefly over property, prejudice, and honor. This Hobbesian war of all against all seems to require the force of a Leviathan like Paladin to bring peace.[42] Paladin has to be the man on the horse, the great leader who can bring the common people out of bondage, but always on his own terms. And standing behind his benevolence, and underwriting it, is the power of his gun, which he does not hesitate to use when necessary (and, of course, he makes the decision when exactly to use it).

In making such decisions unilaterally, Paladin epitomizes the intellectual elitism that characterized both Star Trek and the Kennedy Administration. As we have seen, Roddenberry himself spoke of Paladin’s “detached and superior, sometimes almost condescending, perspective from which he viewed the fallible world about him.” For all his sympathy for common people, Paladin is not a man of the people. Despite his capacity for violent action, he is, in fact, an intellectual hero. That is why the Have Gun writers, including Roddenberry, always have him quoting classics of literature and philosophy, as if he were a college professor. He is the sort of hero a writer can love, a hero who loves writers. Paladin is an intellectual’s idea of what a hero should be, or rather, the kind of hero an intellectual would like to be if only he had the power. Free of common people’s prejudices and intellectual limitations, Paladin knows what is truly good for humanity and nobly struggles to achieve a better world for his fellow human beings. No wonder Roddenberry found it easy to project himself into the character Meadow and Rolfe had created.[43]

For the same reasons, Roddenberry readily identified with both Kirk and Spock.[44] All three figures embody an intellectual writer’s fantasy of himself as a superhero. Like many authors, Roddenberry fancied himself morally and intellectually superior to his fellow human beings—“the fallible world about him”—and assumed that, given the power and the opportunity, he could prove his superiority, much to the benefit and admiration of all humanity. If one is looking for a personal touch in Roddenberry’s vision of Paladin and Kirk, evidently he especially liked to fantasize about a hypermasculine hero so irresistible to women that they would constantly throw themselves at his feet in worship.[45] Both Have Gun and Star Trek gave Roddenberry a chance to play out his fantasy life on national television, while at the same time enjoying the moral satisfaction of teaching uplifting lessons in toleration to an admiring public.

There is one more way in which the intellectual’s image of his ideal superhero can teach us something about liberalism, and it is evident in Roddenberry’s impulse to divide up between Kirk and Spock the character elements that were originally combined in Paladin. Spock best embodies the liberal intellectual’s dream of himself—a perfectly logical, detached, and disinterested creature, free of all human passions, capable of coming up with purely rational and scientific solutions to human problems. Spock is the liberal intellectual as social engineer. His calm demeanor reflects the liberal’s inclination to deny that aggressiveness is natural to human beings, or at least to minimize its role in human life. In the liberal vision, aggressiveness is an atavistic impulse, leftover from the bad old days, the undemocratic ages during which wolfish aristocrats imposed their wills on sheepish people. As we see throughout Have Gun-Will Travel, aggressiveness is for bullies, and Paladin’s mission is evidently to rid the Wild West of bullies.

And yet paradoxically, as we have seen, Paladin is a bit of a bully himself, not averse to throwing his own weight around, and unfailingly answering aggressiveness with more aggressiveness. Both Have Gun and Star Trek—and the liberalism they reflect—are premised on the idea that the only thing that cannot be tolerated is intolerance, and prejudice can be eliminated only by force. Thus the liberal hero ends up in a dilemma. He very much needs his aggressiveness, and yet on some level he must deny it and present himself as a man of peace. Thus in Star Trek, Spock turns out to be insufficient as a hero and must always be paired with Kirk, who can supply the element of aggressiveness lacking in the overly rational Spock. Captain Kirk is the living embodiment of the paradoxes of liberalism.[46] He speaks all the time in favor of harmony and cooperation, and yet he is one of the most competitive men imaginable (this aspect of his character is reflected in his compulsive womanizing). He claims to be a tolerant man, but he will not tolerate challenges to his authority as captain of the Enterprise. In political terms, Kirk is ambitious for office, and continually fights to stay in power. He reveals the aggressiveness that a political man must have if he is to gain power and accomplish anything in the public sphere. This is one more way in which Kirk mirrors his model, John Kennedy, and highlights a contradiction in liberals—their unwillingness to acknowledge their own aggressiveness, even though it is necessary to fuel their ambition and drive their liberal programs.

Liberals tend to exempt themselves from their view of humanity as hopelessly mired in the prejudices and aggressiveness of the past. If everyone else is corrupted by base motives like greed and ambition, why should we expect liberals alone to be free of these human foibles? As we have seen, Have Gun-Will Travel asks us to believe that every rich man in the West is corrupted by money except Paladin. The record of liberal politicians like John Kennedy in office raises genuine doubts about whether their high-minded goals insulate them from the traditional failings of ambitious men. Paladin comes too close to revealing the contradictions at the heart of the liberal character and the liberal agenda. By dividing up Paladin into Spock and Kirk, Roddenberry was to some extent able to conceal these paradoxes and to maintain in Spock the purity of the liberal’s self-image as intellectually superior and free from ambition and aggressiveness. Thus Have Gun in many respects offers a more complex view of the world than Star Trek does because Paladin is a more problematic figure than either Kirk or Spock.[47] Contrary to Roddenberry’s intentions, the conjunction of Have Gun and Star Trek may teach us a lesson in the dangers of a peculiar kind of liberal self-righteousness. Convinced of the purity of his motives and the justice of his cause, a heroic figure may develop a new form of the arrogance of power, perhaps as destructive as the old aristocratic pretensions. Unacknowledged and thus working below the surface of consciousness, a hero’s pride may tempt him into overestimating his capabilities and lead him into perilous situations. This certainly happens to Paladin. Often he must shoot his way out of situations into which his pride has gotten him. As it turns out, “the knight without armor in a savage land” is still a warring knight and still capable of savagery himself.[48]

Who Created Star Trek?

The extent to which Roddenberry’s scripts for Have Gun-Will Travel anticipate his later work on Star Trek may surprise fans of the science fiction series. They like to idolize him as the sole creator of Star Trek, the visionary genius who singlehandedly brought science fiction to television against overwhelming odds. In his public statements, Roddenberry did very little to discourage this exalted view of his role. But if many of his ideas for Star Trek developed in the course of his writing for Have Gun, if, for example, the character of Paladin helped shape his conception of Kirk and Spock, then Herb Meadow and Sam Rolfe in effect contributed to the genesis of Star Trek. After all, they created Paladin, and in writing for their series, Roddenberry was working within parameters they set up. The themes and motifs of the episodes he wrote for Have Gun are very similar to what we find in episodes by the other writers. Given the nature of this essay, I have discussed in detail only Have Gun episodes written by Roddenberry, but I could have made basically the same points by looking at the work of other writers, who just as regularly came up with scripts about lynch mobs, water rights, overweening cattle barons, persecuted minorities, and women for Paladin to charm.

I have followed a different procedure in referring to episodes of Star Trek for comparison. There I have not restricted myself to episodes that were specifically written by Roddenberry. He took a writing credit for surprisingly few of the 79 original Star Trek episodes.[49] My assumption has been that, whether or not Roddenberry is credited with writing a particular episode, they all reflect his influence. As the creator/producer of Star Trek, he came up with the basic framework for the series, and set up guidelines for anybody writing scripts for it and enforced them carefully. As a hands-on producer, he worked closely with all the writers, sometimes throwing out suggestions to them, always shepherding their scripts through production—a process that in television necessarily involves a great deal of rewriting, which Roddenberry often did without taking a writing credit for himself.[50] According to all accounts, every Star Trek episode bears the stamp of Gene Roddenberry. That is why in talking about his vision in Star Trek, one does not have to restrict oneself to scripts that officially carry his name. But that means in turn that the scripts Roddenberry wrote for Have Gun-Will Travel all bear the stamp of Herb Meadow and Sam Rolfe. And one must not discount the efforts of a variety of producers and script editors who undoubtedly (and largely anonymously) worked with Roddenberry to polish his scripts as they made their way to the air. If we recognize Roddenberry’s influence on all the writers who worked on Star Trek, then we must acknowledge the influence of the creators of Have Gun-Will Travel on him as a writer for the earlier series and thus by extension their ultimate influence on the later series. Whatever his fans may think, Star Trek did not spring magically out of Roddenberry’s solo imagination.[51]

As we have already seen, when he thought it would help, Roddenberry tried to pass himself off as “head writer” of Have Gun-Will Travel, even though Sam Rolfe has made it clear that no such position ever existed.[52] A good deal of evidence suggests that throughout his career, Roddenberry had a tendency to take more credit for his writing accomplishments than he fully deserved.[53] We need to do a better job of putting his achievement in perspective. For Have Gun he was part of a very talented team of writers (several of whom also went on to write for Star Trek).[54] More generally, in working on the Western, he was teamed up with producers and directors, all of whom played a significant role in making the series a success. The record shows that in the case of Have Gun, its star, Richard Boone, was unusually active for an actor in shaping the development of the series and insisting on maintaining its quality. He even directed many episodes himself.[55] By the same token, actors like William Shatner and Leonard Nimoy clearly put their stamp on Star Trek and surely deserve some of the credit for the success of the series.[56]

In sum, like any TV series, Star Trek was not the one-man show Roddenberry’s admirers often take it to be. We tend to come to popular culture with a paradigm of solitary authorship ultimately derived from Romantic poetry.[57] We want to picture television writers on the heroic model of the lonely misunderstood genius we are familiar with from the self-image of poets like Byron and Shelley. But the fact is that, like most of pop culture, television is very much a collaborative medium and it succeeds precisely by pooling the talents and resources of many creators at once. In a moment of candor, Roddenberry himself acknowledged this aspect of pop culture in a letter to a colleague:

In fact, it seems that our business violates the one basic rule of all businesses, i.e. that committees can never accomplish anything. In almost any other work, creativity always ultimately reduces itself to one man doing the job. Here we have a half dozen or more creators, all contributing. The producer can guide them but he dare not do much more.[58]

The history of both Have Gun and Star Trek confirms this understanding of the collaborative nature of creativity in television. It does not call into question Roddenberry’s creativity to point out that, in working on both shows, he was not operating alone but constantly depended on and learned from his colleagues, repeatedly benefiting from their advice and example, and often drawing upon their ideas. Perhaps Roddenberry’s true genius was his knack for taking advantage of the pool of creative talent in Hollywood.[59]

Science Fiction—Forget About It

The links between Roddenberry’s work on Have Gun and his creation of Star Trek bear on another issue that has been raised, the question of whether he truly was a science fiction writer. It may seem preposterous to wonder whether the creator of arguably the most popular science fiction vehicle of all time should be legitimately regarded as a science fiction writer. But there are, in fact, legitimate grounds for controversy here. David Alexander, the writer of Star Trek Creator, the authorized biography of Roddenberry, goes out of his way to establish Roddenberry’s credentials as a science fiction writer, asserting, for example (with somewhat limited evidence), that Roddenberry’s interest in science fiction went all the way back to his youth.[60] Once Star Trek made Roddenberry famous, he eagerly claimed admission to the fraternity of science fiction writers and took great pride in his friendship with giants in the field, such as Isaac Asimov and Arthur C. Clarke. But at least one critic, Joel Engel, in his decidedly unauthorized biography of Roddenberry, has argued that the creator of Star Trek became a science fiction writer by accident. Engel points out that the bulk of Roddenberry’s early writing for television was for cop shows and Westerns, and that he wandered into the area of science fiction simply in his continuing search for a successful TV formula. Engel questions the depth of Roddenberry’s familiarity with traditional science fiction, and claims that he had to pump friends and colleagues for knowledge in the area when he finally set about working up Star Trek.[61]

The fact that we have seen Roddenberry developing the basic elements of Star Trek while working on a TV Western does raise some doubts about how fundamental science fiction was to his vision as a writer. Roddenberry’s anxiety about his credentials as a sci-fi writer may explain why, as we have seen, he chose to baptize Paladin retroactively as a science fiction figure, almost as if he were trying to reassure people: “I’ve been writing science fiction all my life; it just looked like a Western.” But elsewhere, Roddenberry reversed his position, claiming that what makes Star Trek good is not its science fiction aspects. Amazing as it may sound to his admirers today, he instructed his authors not to think of themselves as writing science fiction when working for the show. Consider these excerpts from a long memo he wrote to the agent of one of his Star Trek writers:

We are asking of the writer no more than any other new show asks and must have, i.e. study what is available on the lead characters, his attitudes and methods, the secondary characters, the inter-relations, and those basic things you would have whether this was the beginning of a Western, hospital drama, or cops and robbers. . . . At this point, we not asking [the writer] to write science fiction! We are asking him to give us quality in how he draws his characters, in making our regular people act and interact per our format with which he has been amply provided, to give them the “bite” of their individual styles, to have the Captain (like Matt Dillon or Dr. Kildare even) act like what he is, and above all, again forgetting science fiction, have everybody use at least simple Twentieth Century logic and common sense in what they look for, what they comment on, what surprises them, how they protect themselves, and so on.[62]

I quote this memo at length not just for the shock value of seeing Roddenberry telling one of his authors to forget about writing science fiction.[63] It is actually a fascinating document—a rare opportunity to see in writing the kind of detailed instructions showrunners have undoubtedly been giving orally to writers ever since the beginning of television. As Roddenberry continues, we see clearly that he conceived of Star Trek on the model of another TV Western, Gunsmoke (1955-75):

For example, as you will see in the script, we are in an Earth-like city which stopped living some centuries ago. And yet, as they land there, no one comments on the strange ancient aspect of it. For God sakes, if Matt Dillon came upon an Indian village which had been deserted for even three or four years, he or Chester or someone would at least be aware of that fact.[64]

Evidently, in thinking about a good show, Roddenberry asked himself: “What would Matt Dillon do?”[65] In general, in analyzing good writing, he abstracted from the question of genre. To him the same rules of exposition, character development, plot construction, and believability govern Westerns, hospital dramas, cop shows, and science fiction alike.

In what would today be called the Star Trek Bible, the Writer-Director Information Guide Roddenberry prepared for anyone interested in working on the show, he makes his position clear: “Science fiction is no different from tales of the present or the past--our Starship central characters and crew must be at least as believably motivated and as identifiable to the audience as characters we’ve all written into police stations, general hospitals, and Western towns.”[66] The loyal science fiction fans of Star Trek might be shocked to see Roddenberry’s formulation of the prime directive that governed the scripts. He laid down the law of what makes for a bad Star Trek story in these terms: “They fail what we call our ‘Gunsmoke-Kildare-Naked City Rule’—would the basic story, stripped of science fiction aspects, make a good episode of one of these shows?”[67]