Myths of Creation Introduction

On the most general level, this course is a study in literary mythmaking. It’s a curious phenomenon of modern culture to see sophisticated artists imitating the most primitive form of human expression—myth. “Literary myth” almost seems like a contradiction in terms. Myths don’t have authors; they’re thought of as communal efforts, not conscious artistic products. They well up out of the depths of the folk-soul. No one is in control; myth is a case of primitive man experiencing his environment expressively. Modern man prides himself on having advanced beyond the need for myths. Enlightenment means that all truths can be apprehended on the level of rational discourse. There’s no longer a need to turn to stories or legends that embody an understanding of the world in affective form. Progressive theologians today even pride themselves on their ability to demythologize their religions. Yet myth persists in our culture. The power of mythmaking has never been quite extinguished in literature, though it has reached some rather low ebbs at times.

There are different forms of literary mythmaking. One is in fact difficult to distinguish from primitive mythmaking. We have access to the myths of many cultures through what are clearly sophisticated literary documents. The Iliad and the Odyssey are outstanding examples of this; Hesiod’s Theogony is another case. Consider the Norse Eddas or the Akkadian Epic of Gilgamesh. In these cases, it is difficult to determine to what extent the authors in question are simply recording myths they found already developed in their culture, and to what extent they created the myths or at least modified them substantially in the course of shaping them up artistically. It’s important to remember: sometimes when we’re looking at what we think to be primitive myths, we’re actually dealing with relatively late products of a culture, which have already passed through the formative agency of an artistic consciousness, such as Homer’s. It’s an enviable position for an artist—to have first crack at giving form to the myths of his people. If he does his job well, no one else may ever again get a similar opportunity. Consider Homer’s role in shaping what we today think of as Greekness. This is not just our perspective on the matter. The discussion of the education of the guardians in Plato’s Republic centers on how to impart to them salutary opinions concerning the gods and that turns on the issue of what to do about the presentation of the gods in Homer’s poetry. As Socrates presents it, the re-education of Greek youth means reworking the myths of Homer. This shows us the degree of influence and prestige his poems had attained among the ancient Greeks in Plato’s time.

This kind of myth-making—what one might call primary myth-making—is obviously not open to all authors. It requires fortuitous circumstances. Normally most artists are confronted with a body of ready-made myths, which are generally accepted and can at most be modified. This situation leads to what one might call secondary mythmaking. These artists work within a clearly established mythic tradition, sometimes codifying existing myths, elaborating them, using them for assorted entertainment or didactic purposes. This is the sort of thing you get in writers like Ovid and his Metamorphoses. This is a sophisticated art form, sophisticated sometimes to the point of decadence. Myths may serve a purely decorative function, dressing up prosaic thoughts and sentiments in the fancy clothes of ancient myth. We find a great deal of this in 18th-century English literature. This can lead to staleness and sterility—stock characters, stock situations, stock language. This eventually degenerates into parody—writers making fun of the conventional use of mythology. Look at the famous opening of Book One, Chapter VIII of Henry Fielding’s novel Joseph Andrews: “Now the rake Hesperus had called for his breeches, and having well rubbed his drowsy eyes, prepared to dress himself for all night; by whose example his brother rakes on earth likewise leave those beds in which they had slept away the day. Now Thetis, the good housewife, began to put on the pot, in order to regale the good man Phoebus after his daily labours were over. In vulgar language, it was in the evening when Joseph attended his lady’s orders” (Fielding 35). We see here a writer who’s been mythologized to death, and is sick of hearing mythic invocations. He realizes that myth is being used merely to puff up the most ordinary material. When mythmaking has reached this stage—where it’s just an object of parody—it’s more or less at a dead-end. At this point, one would expect literary mythmaking to die out entirely or a new body of myth somehow to come into existence and start the cycle all over again.

But there is another possibility: the attempt to revitalize a body of myth by reinterpreting and transforming it, in short, by recreating it. This is what happened in 19th-century European literature. It is basically this kind of Romantic myth-making that we will be studying in this course. One way of looking at the phenomenon of Romanticism is this: literature had reached an impasse. The vital sources of mythic inspiration had dried up. The Romantics wanted to be able to draw upon the power of myth in their art, above all, to give a cosmic dimension to their work, to be able to deal with the big issues. Also to be able to speak, not just to the intellect, but to the emotions. And finally to be able to speak to the mass of humanity. For all this, they felt that it was necessary to speak mythically. To do that, they had to find new meaning in the old myths. This leads to a process of inner transformation of the old myths—in essence, what amounted to an inversion of their values. The old gods became devils, the devils became gods. This may seem arbitrary if looked at as a purely aesthetic phenomenon, as if some young whiz-kid at the Romantic Writers’ Guild suddenly had the brilliant inspiration one day of inverting the pantheon: “Hey guys, let’s make God into the devil and the devil into God for a change.” But Romanticism was by no means a purely aesthetic phenomenon. There were strong philosophical and ethical motivations behind the new mythmaking. For the Romantics, the old gods were tied up with the old regime. Religion provided some of the prime support for the corrupt aristocracy in Europe; piety was being used to keep people subjected to their earthly rulers. The Romantics were by and large revolutionaries and they understood that complete rebellion requires the overthrow of the old gods. That in fact was seen as the necessary prelude to any form of political liberation in Europe. Now of course what the Romantics had particularly in mind was the overturning of Christian orthodoxy, but some of them, especially Blake, felt that Geek myths had become part of European orthodoxy too in the moralistic uses to which they had been put. So for Blake the Greek myths had to be overturned, too.

In this larger context, the inversion of traditional mythic values no longer appears to be arbitrary. Romanticism is rooted in an animus against traditional religion, and the creation of new myths was a necessary part of the Romantic program. Harold Bloom raises this question in his book Shelley’s Mythmaking: “Which has primacy: the mythmaking impulse and commitment to the mythopoeic mode, or the religious position counter to that of Christianity?” (9) In other words: do the Romantics hate orthodox religion because it stands in the way of their creating new myths or do they want to create new myths in order to get orthodox religion out of the way? This dilemma easily resolves itself. Why would the Romantics want to create new myths? Because they put a value on creativity. What do they see as hostile to their creativity? The old regime, and that includes orthodox religion. The will to create new myths and the hostility to orthodox religion stem from the same root—the new premium on creativity. That is why in studying Romantic myth, it is particularly important to study Romantic myths of creation. The best way of attacking orthodox religion is at its foundations. Attack the orthodox account of Genesis. Offer new accounts of the Creation. At the same time, developing a new account of the creation offers a chance to develop the idea and ideal of creativity, which is the ideal of the modern world.

It is significant that the creation myth or theogony develops into a sort of genre of its own in 19th-century literature. It’s a small genre to be sure, and we’ll be reading most of the main examples of it. But it includes some of the most significant and magnificent products of the Romantic imagination, works that absorbed the energies of Blake, Percy Shelley, Byron, Keats, and Wagner. If you’re interested in creating myths, obviously myths of creation take on a special importance. They establish the context in which all other myths take place. Creation myths may be the most abstruse and remote myths, the furthest from everyday experience, but they reveal where our everyday experience comes from. As we will see, the Romantics use the creation myth as a means of exploring the question of why we experience the world the way we do. They want to show how man’s vision has been narrowed—that will then serve as a prelude to a new liberation of the senses. For the Romantics, the current human situation is not one of freedom. Rather, man’s best impulses seem dammed up and perverted as a result of repressive morality. Romantic creation myths are designed to account for this; that is why they involve an inversion of traditional mythic values. For poets like Blake and Shelley, the original act of creation was an act of evil, not of good. The “divine” creation is responsible for the misery of the human condition. It was an attempt to restrain man’s energies, to tie down his spirit. It was like chaining him up in a cave and cutting him off from all visions of a higher world. Thus for the Romantics, the creator-god of traditional religion comes to be identified as a demonic figure, if not the devil himself. And all those who are willing to rebel against the order of creation—that is, the figures known as devils in the orthodox religious accounts—become in the Romantic myths the saviors of humanity, if not the gods themselves. The specific pattern of Romantic myths—the inversion of values—stands most clearly revealed in their creation myths.

Here’s a brief outline of the course and explanation of the reading list. We will begin with some traditional creation accounts, to show what the Romantics ultimately were reacting against. We’ll begin with Hesiod’s Theogony—the grandaddy of them all—which can serve as the prototype of a primitive creation account (even though it achieves a certain level of literary sophistication). Genesis and Plato’s Timaeus represent more sophisticated attempts to deal with the problem of creation. Both rise above the level of mere myth and embody significant understandings of the human condition in the form of creation myths. They epitomize the two great traditions in Western culture—the biblical and the classical. We can find most of what makes these traditions rivals evident in their rival accounts of creation. The Romantics rebel against both traditions, but, as we will see, they break more radically with the classical tradition than with the biblical. Then we will look at the problem of evil, dealing with the troubling question: if the creation was good, why is man in such bad shape? We will look briefly at an early religious movement known as Gnosticism. In Hans Jonas’ book The Gnostic Religion, we will find prototypes of much of what occurs in Romantic mythmaking. Finally, by way of preparation, we will look at the greatest literary monument of the biblical creation account, John Milton’s Paradise Lost. Paradise Lost is the form in which most of the Romantics confronted the problem of creation. Many of the works we will read can be viewed as attempts to rewrite Paradise Lost: Blake’s Book of Urizen, Percy Shelley’s Prometheus Unbound, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, Byron’s Cain, Keats’s Hyperion poems.

Before getting to these Romantic creation myths, we will discuss how the traditional creation accounts began to be challenged in modern philosophy, focusing on David Hume’s attack on natural religion and Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s new account of how man as man came into being. By portraying the origin of man as the result of the accidents of history rather than a benevolent providence, Rousseau opened the way for the idea that man can actually improve upon his original condition via his own efforts. Rousseau thus laid the foundation for the Romantic ideal of self-development. His Second Discourse is fundamental to any understanding of Romanticism—perhaps the single most important work in this area.

We will then begin our study of Romantic creation myths with William Blake, one of the focal points of this course. We will spend more time on him than any other author; he shows most clearly what was involved in Romantic mythmaking. Blake reflected on the whole problem of myth. He gives reasons for taking the mythic approach that he does. We will concentrate on his Book of Urizen, a very dense and abstruse myth of creation (some 14 pages). It requires detailed explication. Blake portrays a botched creation. The human condition is the result of the bungling of a misguided deity, an impotent creator, perhaps even a demonic creator. Blake’s deprecation of divine creativity is linked to a new premium on human creativity. If the traditional God botched the creation, man is free to improve on it. We will see very similar ideas in Shelley’s Prometheus Unbound. Working independently of each other, Blake and Shelley came up with remarkably similar mythic patterns in their poetry. That is one clear sign that a new spirit in mythmaking was shared by the Romantics.

Romantic theogonies were designed to release man’s long pent-up creative energies. The Romantics expected a transformation of the human condition as a result—an apocalypse. Their great hope was that the artist can liberate humanity. Soon, however, fears developed about this liberation. What exactly is being liberated? Is the artist able to bear his new freedom? Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein offers a nightmare vision of what it is for man to try to replace God’s creativity with his own. Byron’s Cain, Wagner’s Ring of the Nibelung, and Keats’s Hyperion poems all in some way deal with the loneliness, isolation, and tragic suffering of the Romantic creative ego. This is especially clear in the Ring, where the myth of a creator-god becomes a projection of the artist’s own ego, an attempt to come to terms with his own creativity. The Romantics discover that it’s not only the creator-gods of traditional religion who have problems. In their attempt to replace the old gods, the Romantics find that they inherit many of their old problems. The Romantics found dubious motives in the traditional creator-gods, a dark side. Then they find the same thing in themselves.

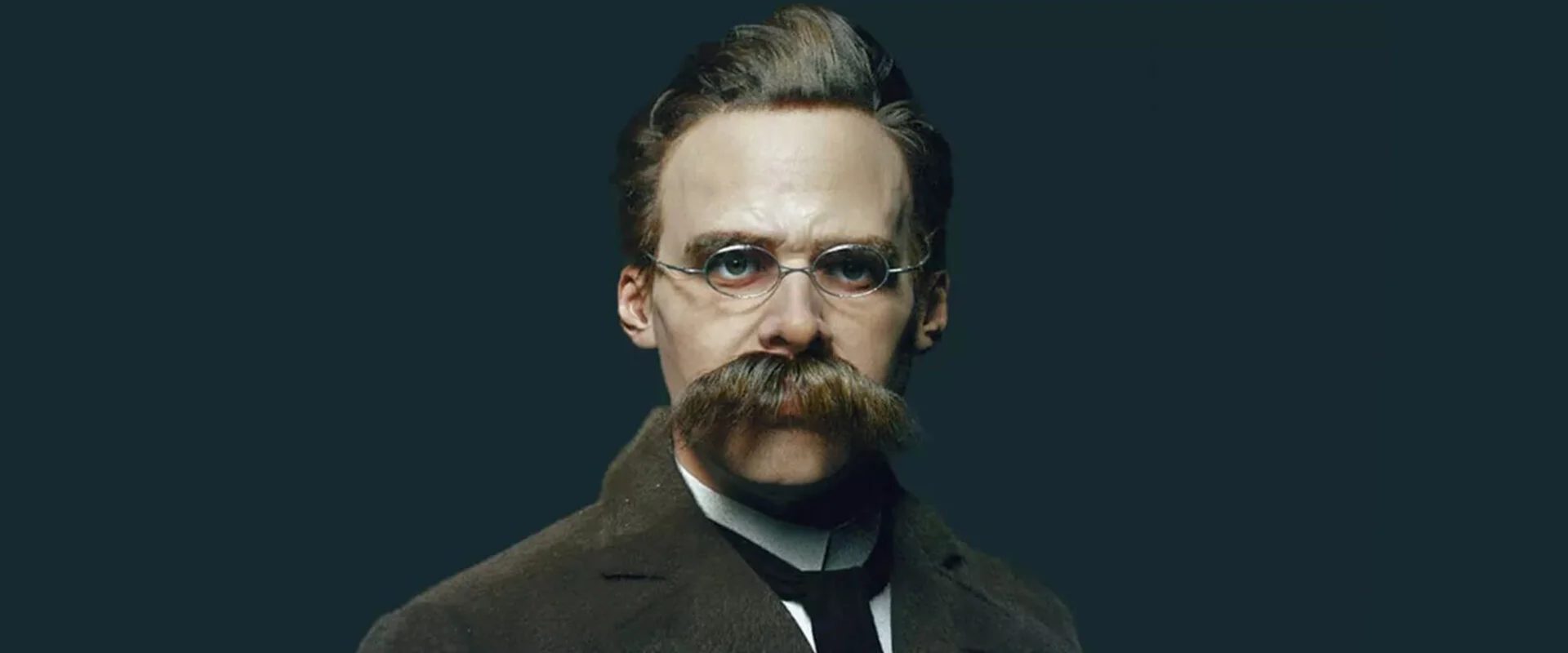

Friedrich Nietzsche is one of the other focal points of the course and will provide us with a new beginning. He shows how Romantic myths of creation are connected with 20th-century literature. One aim of this course is to show the continuity in 19th- and 20th-century literature. The categories we use in literary history—Romantic, Victorian, modern, and postmodern—are largely artificial and to some extent arbitrary. Studying the creation myth offers a good opportunity to observe the continuous development of one set of themes from Hume and Rousseau right up almost to the present—John Barth.

With Nietzsche, we will read his most famous book, Thus Spoke Zarathustra. In some ways, this book is a continuation of Romanticism; it offers the most radical statement of the primacy of human creativity. Nietzsche’s hostility to traditional religion is even greater than that of the Romantics. He is even more determined than the Romantics to replace divine creativity, as traditionally understood, with human creativity. But at the same time, Nietzsche offers a thoroughgoing critique of Romanticism and a break with its apocalyptic hopes. Nietzsche in fact does without a myth of creation. He replaces it with a new myth—the myth of the eternal recurrence of the same. The whole dramatic movement of Thus Spoke Zarathustra leads up to the embrace of this new myth. We will have to see why Nietzsche thinks this myth provides a better foundation for the ideal of human creativity. The notion of the eternal recurrence supplies the metaphysical framework for much of 20th-century literature, or rather the lack of a metaphysical framework. We can observe this most clearly in William Butler Yeats, the poet of a Nietzschean world. Yeats explores the problems and paradoxes of the Romantic ideal of creativity, with particular regard to the situation of the artist in the modern world. Yeats takes us to the brink of the phenomenon Nietzsche predicted would dominate the 20th century—nihilism—the loss of a sense of value or meaning to life. It is important to trace the way the Romantic attempt to establish all value on a purely human basis eventually leads to nihilism. We find the most uncompromising expression of the modern position in the writings of Samuel Beckett, culminating in perhaps his greatest work, his Trilogy, and especially in the third novel, The Unnamable. This bizarre work turns out to be in the mode of Romantic theogony. The myth of a bungled creation becomes a natural vehicle for expressing Beckett’s absurdist vision of the human condition. John Barth’s Lost in the Funhouse provides an appropriate dead-end for our course, as we see Barth attempting to portray the dead-end literature has worked itself into in our time. In what amounts to a return to Hesiod, Barth weaves together themes of cosmic and sexual generation, and moves from a malevolent creator to an impotent creator.

To sum up the importance of the creation myth as a form: it articulates man’s understanding of his place in the universe. Plato’s Timaeus offers the classical view: man is part of an ordered cosmos; man is basically at home in this world. In the biblical view, man is only partially at home in this world, or perhaps this world is only a temporary home for him. The biblical creation account introduces a whole new dimension—a creator-God who completely transcends his creation. The biblical God exists on a different plane of reality. In the Greek view, the gods are part of the cosmos; they don’t stand above it. More biblical than classical, the Romantic creation myths reflect a gnostic sense that man is not at home in the world as presently constituted. This is the key significance of the genre of theogony in modern literature. It becomes the means of expressing feelings of cosmic alienation, the nagging sense that this world was not made with man’s benefit in mind, that man himself was not made such that he can be happy. His impulses do not seem to be spontaneously in harmony with the demands of the world he’s placed in. These doubts are expressed in the vision of an incompetent or malevolent creator-god. This seemingly pessimistic view of where the universe comes from, leads, however—almost paradoxically—to an optimistic view of where it is heading. By understanding how the original creation was bungled, man will be free to re-create his world and more importantly re-create himself.

The Romantics hope for a kind of new heaven on earth. As the 19th century wears on, however, these hopes begin to dim, as we witness the start of the tedious process known as Waiting for Godot, waiting for the promised apocalypse to arrive. The fact that this transformation of the human condition into something paradisaical fails to happen leads to despair, which leads to a new transformation of the meaning of the creation myth. For the Romantics, man is not at home in this world, but he can make it into his home, remake the world in human form, bringing the world into accord with human desires. 20th-century writers offer basically the same vision of the world as the Romantics presented, but without the hope of transforming it. Man is simply not at home in his world, but there is no world beyond this to which he may aspire, and no world above it like the traditional heaven, and no world off in the historical future, as promised in Romantic visions. Only the same world over and over again—that is the meaning of the eternal recurrence in Nietzsche. Coming to terms with this understanding of the human condition becomes the problem for modern writers. This is the problem of nihilism. The notion of the eternal recurrence seems to pull the ground out from under all human values. If everything is simply fated to repeat itself, why strive for anything? Take away the notion that the cosmos is moving toward an end and it becomes difficult to provide support for human ends. The difficulty for modern writers is finding a new foundation for human values. We will see Nietzsche and Yeats working on this problem. That then is the question I want to look at in considering the relation between Romanticism and modernism. For the Romantics, the creation myth serves as the foundation for human creativity. But there seems to be an internal logic in the development of Romanticism that transforms the creation myth until it threatens to undermine the ideal of human creativity. But to get to the end of our story, we must begin at the beginning, with the ancient Greek and Hebrew understandings of how the world came into being.