Against Chivalry

April 23, 1616 — a date which will live in infamy. At least in literary circles. For on that date both Miguel de Cervantes and William Shakespeare died. To be sure, they did not die on the same day. At the time, Spain had adopted the new Gregorian calendar, while England was still on the old Julian calendar. That meant the calendars in Spain and England were out of sync in 1616, and in fact Shakespeare and Cervantes died 11 days apart. Complicating matters further, most scholars now insist that Cervantes actually died on April 22 and was buried on April 23.

So let's just say that literature suffered a bad two weeks in spring 1616. In any case, the world is now commemorating the 400th anniversary of the deaths of Cervantes and Shakespeare. They had more in common than just the sheer greatness of their literary achievements. Cervantes did not know Shakespeare's work, but Shakespeare almost certainly knew Cervantes's most famous work, Don Quixote. There is solid evidence that in 1612-13 Shakespeare wrote a play called Cardenio (probably in collaboration with John Fletcher). The play has been lost, but the title was recorded in contemporary annals. If Shakespeare did write a Cardenio, it was very likely based on one of the interpolated tales in Don Quixote, one that features an unfortunate lover named Cardenio.

We can only hope that someday a text of Shakespeare's Cardenio will be found in a dusty attic somewhere— stranger things have happened. What a thrill it would be to see one genius re-creating the work of another, and to get a concrete sense of Shakespeare's relation to Cervantes. In the absence of such a find, we can only speculate on the subject. I will argue that Cervantes and Shakespeare did have much in common and that in many respects the two greatest authors of the Renaissance were pursuing the same literary program. They wanted to break free from what they both perceived to be the baleful heritage of the Middle Ages.

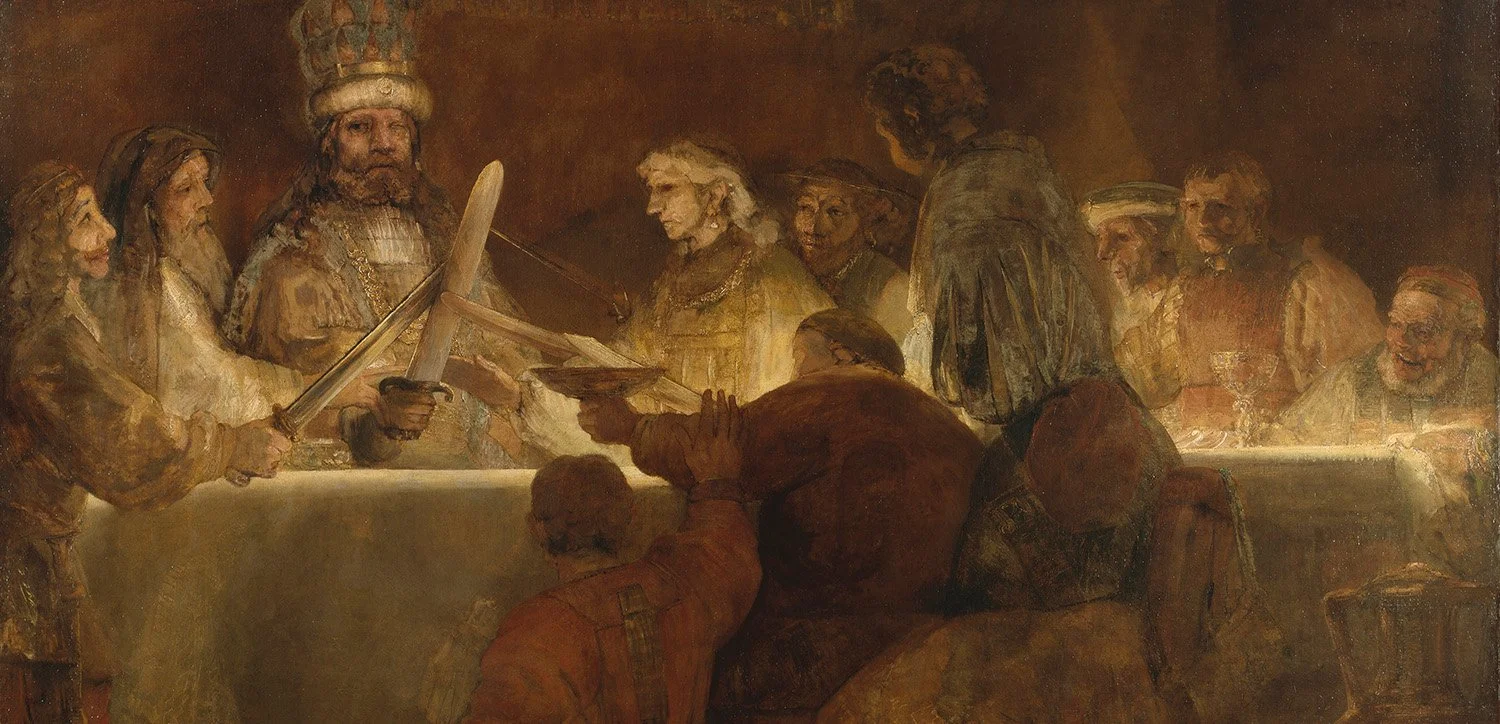

The target Cervantes and Shakespeare attacked was the grandest myth of the Middle Ages: chivalry. It was a noble ideal and at its best it did much to refine an otherwise coarse and brutal world, but it rested on shaky foundations and had many unintended and disastrous consequences. Chivalry was a way of life, a distinctive mode of conducting both war and love. In its purest form, it tried to reconceive war as in the service of love. In literature, the chivalric ideal was embodied in figures such as Sir Lancelot, who, in his noble devotion to Queen Guinevere, always fought on her behalf and in her name.

Chivalry was an attempt to give a religious dimension to all aspects of life — to saturate the world with Christianity. The famous chivalric romances sought to civilize war, to temper its savagery with Christian notions of mercy. As chivalric romance developed, the Quest for the Holy Grail became one of its dominant motifs, giving a spiritual and deeply Christian goal to the knights' striving. Chivalry was bound up with courtly love. A knight was supposed to worship his lady from afar and undergo a spiritual discipline, a quasi-religious purification, in his quest to perfect himself for his mistress's sake. In chivalric romance, the earthly sexual impulses that ordinarily fuel love between man and woman are redirected in a heavenly direction.

All this sounds very elevated and uplifting to us today. Why did Cervantes and Shakespeare feel a need to criticize the medieval idea of chivalry? By demanding so much of human beings, by holding them to an impossibly high standard of conduct, chivalry lost touch with reality. It threatened to distort the common-sense understanding of down-to-earth human affairs and to unleash the dark side of human nature by pretending that it did not exist. In the Middle Ages, chivalric warfare was linked to the idea of the crusade. War became holy war. The attempt to spiritualize warfare turned it into something more brutal by making it fanatical. Cervantes in Don Quixote and Shakespeare in his English history plays call the crusader ideal into question and show the catastrophic results of mixing religious and military motives — more generally of mixing religion with politics.

Similarly, the ideal of courtly love— as developed by the troubadour poets of France and their successors, Dante and Petrarch, in Italy — sought to fuse erotic and religious experience. These authors introduced a new range of emotions into love poetry and opened up spiritual depths never before explored in literature. But by demanding so much of love — no less than spiritual and even divine perfection — they made the ordinary relations between men and women, on which the future of the human race depends, seem crass and base by comparison with the poetic ideal. The dream of a perfect love left men and women dissatisfied with conventional forms of romance, particularly the commonplace institution of marriage.

Courtly love was hostile to marriage and any conventional satisfaction in love. It celebrated infinite yearning and thus called for suffering in love — intense, prolonged, agonizing, hopeless, tragic suffering, since reality can never measure up to the poetic ideal. Cervantes in Don Quixote and Shakespeare in Romeo and Juliet and his comedies portray what goes desperately wrong when lovers take their idea of love from books, when they chase after the windmills of poetic romance rather than settling down to the business of falling in love with real people, founding families, and thereby taking their place in society.

Cervantes and Shakespeare saw that chivalry was one area of life where they, as authors, could make a difference — because chivalry was a literary ideal, formulated and propagated in books. An ideal that grows out of books can be defeated in books. Medieval chivalry is perhaps the greatest example in history of life imitating art, with predictably disturbing results. If a real King Arthur ever existed, he bore no resemblance to the courtly figure who emerged in chivalric tales from Marie de France and Chrétien de Troyes all the way to Thomas Malory. Ideal knights like Lancelot and Tristan appeared first in fiction, and only then were imitated by people in the real world, primarily in forms of courtship, but even in forms of combat. Knights were jousting in tournaments in books long before they ever pointed lances at each other in the real world.

The attack on chivalry in Cervantes and Shakespeare is clearest in Don Quixote, but to understand that we must first put aside the image of Don Quixote that prevails today. Cervantes's Don Quixote has a hard edge. It is a nasty, cruel book. It really makes fun of Don Quixote, showing him to be a fool and a dangerous fool— a danger to himself and a danger to others. This was the way Don Quixote was understood up until the 19th century. It was only the Romantics who— recognizing a kindred visionary dreamer in Quixote — began to idealize the Don, to romanticize him. They took the figure of ridicule in Cervantes's book and turned him into a Romantic hero.

By the 20th century, this process of transforming Cervantes's character into its opposite was completed by sentimentalizing him, and the result was Man of La Mancha. "To dream the impossible dream" is exactly the idea Cervantes is satirizing, but on Broadway it became an anthem celebrating Don Quixote and his idealism. People who know his story only from the Broadway musical are surprised, if they ever read the original novel, to discover that the divine Dulcinea never even appears in Cervantes's version — she is only talked about — and she certainly does not join Don Quixote for a tearful reunion on his deathbed. Cervantes offered Don Quixote, not as a model of heroism, but as a cautionary tale of an overheated imagination, hopelessly out of touch with reality.

Don Quixote tells the story of a man who goes crazy from reading too many books of chivalry, books like Amadis of Gaul, thus developing a false view of the world. In the prologue, Cervantes has a friend state explicitly the purpose of the book: "to destroy the authority and influence that books of chivalry have in the world"; the goal is "overthrowing the ill-based fabric of these books of chivalry" (Walter Starkie translation). In Part II, chapter viii, Cervantes has Don Quixote state openly: "Chivalry [ caballería] is a religion." The religious dimension of Don Quixote's chivalry emerges quite clearly in an incident in Part I, chapter iv. The knight encounters a group of silk merchants from Toledo on the road, and "imitating as closely as possible the exploits he had read about in his books," Don Quixote boldly challenges them: "Let all the world stand still if all the world does not confess that there is not in all the world a fairer damsel than the Empress of La Mancha, the peerless Dulcinea of El Toboso."

The merchants are startled by this challenge but decide to humor the madman confronting them: "Sir knight, we do not know this lady you speak of. Show her to us, and if she is as beautiful as you say, we shall willingly and universally confess the truth of your claim." But Don Quixote will not accept these common-sense conditions: "If I were to show her to you, what merit would there be in acknowledging a truth so manifest to all? The important point is that you should believe, confess, affirm, swear, and defend it without setting eyes on her." In short, the silk merchants must accept on faith Don Quixote's word that Dulcinea is the most beautiful woman in all the world. They must believe in things unseen — or suffer dire consequences at Don Quixote's hand.

This passage is saturated with religious language; Don Quixote even accuses the merchants of "blasphemy" when they fail to fall in line with his worship of Dulcinea. This scene epitomizes Don Quixote's mission: to convert the whole world to his religion of love — by force, if necessary. When I once presented this interpretation at a conference on Don Quixote, a genuine Cervantes scholar pointed out that in the 16th century in Spain, silk merchants from Toledo would have been identified with conversos, Jewish converts to Christianity. In 1492, all Jews were expelled from Spain. Those who wanted to remain had to become Christians, or at least to give the appearance of having done so. Such was the fate of the Jewish merchants engaged in the silk trade in Toledo if they wished to stay in business. Behind the comic encounter between Don Qui-xote and the silk merchants looms the very serious issue of religious conversion, an issue that was tearing Europe apart in Cervantes's day, whether in conflicts among Christians, Jews, and Muslims or between Protestants and Catholics within the Christian camp. The absolute demands for religious conversion were producing holy war in Europe.

The idea of holy war runs throughout Don Quixote, especially with its many mentions of the Spanish Inquisition. The book frequently refers to the Spanish Empire and its efforts in the New World to convert the natives to Christianity. Readers today may be surprised to learn in Part II, chapter viii, that Don Quixote admires the conquistador Cortez; he calls him "most courteous," on the model of a chivalric knight (not as strange as it sounds; we know for a fact that the conquistadors read books of chivalry, including Amadis of Gaul).

In modern recreations, Don Quixote's adventures may seem like harmless fun, but in the original version, they take on ominous implications. What could be more ridiculous than Don Quixote's attack on the windmills in Part I, chapter viii? But here is how the knight presents the windmill-giants to Sancho Panza: "With their spoils we shall begin to be rich, for this is a good war and the removal of so foul a brood from off the face of the earth is a service God will bless." This combination of mercenary and religious motives perfectly characterizes the behavior of conquistadors like Cortez and Pizarro in the New World. Given the genocidal effects of Spanish imperialism, perhaps we should not find it so amusing when Don Quixote cavalierly speaks of exterminating a race on religious grounds. Don Quixote's lunatic adventures are Cervantes's image of the Spanish Empire run amok in holy war, redirecting the medieval crusading spirit to the conquest of the New World, with brutal consequences for the native population.

In a single book, Don Quixote relates chivalry in war to chivalry in love and shows how toxic the combination of religion and politics can be. To get the whole world to convert to your religious view is a quixotic quest, and the collapse of Spanish power in the 17th and 18th centuries proved Cervantes right.

Shakespeare's critique of chivalry is not concentrated in a single book, but is instead distributed throughout his plays. Don Quixote is in fact helpful in showing how Shakespeare's histories are related to his comedies and to Romeo and Juliet. Roughly speaking, the histories criticize chivalry in politics; the comedies make fun of chivalry in love, while Romeo and Juliet reveals its tragic potential.

Richard II opens in the high medieval world of chivalric romance, with knights in shining armor swearing solemn oaths on a field of ritual combat. We seem to be in an elevated world of truth, justice, and the medieval way, with everyone relying on God to settle political disputes via trial by combat. But we quickly learn that all this ceremonial display is a façade, concealing a Machiavellian world of political machination behind the scenes. The king and the nobles are involved in a sordid squabble, and Richard is mainly concerned with the mundane business of raising enough money — by whatever means, fair or foul — to sustain the lavish style of his court and to finance his wars. Richard has a medieval faith that God will support his kingship, and he fails to pay sufficient attention to political reality — his need to maintain the allegiance of the powerful barons with whom he, as a feudal lord, shares military power.

That is why Bolingbroke is able to overthrow Richard and become Henry IV. He realizes that a king is no stronger than the armies that fight for him, and his Machiavellian actions speak louder than Richard's chivalric words. Yet even Henry IV is bewitched by the idea of holy war. He dreams of leading a crusade to the Holy Land and redeeming it from pagan hands. It has been prophesied that he will die in Jerusalem. In a deflating irony, he learns on his deathbed that the prophecy referred merely to a room in Westminster named "Jerusalem." His son, who becomes Henry V, realizes that an expedition to the Holy Land is an impractical and imprudent venture. Still wanting to unite a divided nation behind him in a glorious war, Henry V comes up with a much more practical project — leading his armies against the French just across the Channel and reclaiming the lands of his Plantagenet ancestors. He just barely succeeds in defeating the French at Agincourt, and yet by the end of Henry V, the crusading impulse has awakened even in the most practical of Shakespeare's kings. Anachronistically, Shakespeare portrays Henry hoping to liberate Constantinople from the Ottoman Turks. Only his premature death prevents him from pursuing this quixotic quest, and the English crusading spirit dies with Henry V. Much to Shakespeare's relief.

Shakespeare's history plays chronicle the transition from medieval to modern monarchy, and that involves the increasing secularization of kingship. His kings move from high-minded and idealistic motives for war to Machiavellian concern for realpolitik, and they are successful to the extent that they manage to neutralize the impact of the church and its officials on English politics. Henry V opens with a scene that shows the king using the threat of seizing church lands to get the prelates to support his war policy against the French. This scene foreshadows the subordination of religion to politics that became the cornerstone of the Tudor and Elizabethan regimes. Like Cervantes, Shakespeare sought to get the holiness out of war and politics.

As for his critique of courtly love, in Romeo and Juliet, Shakespeare dramatizes its potential for tragedy. His quixotic hero and heroine have gotten their idea of love from books. Indeed, Romeo's friend Mercutio, seeing him in the grip of love, cynically comments: "Now is he for the numbers that Petrarch flowed in." Romeo and Juliet seek out an absolute love, one incompatible with their ordinary social obligations. They fall in love not despite the fact that their families are feuding but precisely because they are. Courtly lovers to the core, they crave a love that will end unhappily. The only way they can validate the infinite power of their love is to sacrifice everything for it, which means to die for each other. They do not want their love to integrate them into the community — that would be too conventional for them. Instead their love becomes their way of isolating themselves and transcending all conventional social roles. Like Cervantes in Don Quixote, Shakespeare in Romeo and Juliet reveals the destructive power of love when it seeks a radical break with the everyday world of social reality in its quest to achieve an otherworldly transcendence.

Shakespeare's comedies continue his battle with courtly love, this time using humor as his weapon. The action in his comedies forces the lovers to abandon their courtly love conceptions and come to terms with the reality of day-to-day relations between men and women. Shakespeare's comic figures typically begin by over-idealizing love. They must learn to compromise, to give up their unrealistic expectations for love and accept their limited possibilities as imperfect human beings. The comic confusions in plays such as A Midsummer Night's Dream, Twelfth Night, and As You Like It — all the role-changing and especially the gender-bending complications — have the result of breaking the young men and women out of the conventional poses of courtly lovers they learned from books and getting them to recognize that finding a real and available companion for life is preferable to hopelessly questing for a perfect — but unattainable — love. "To dream the impossible dream" is precisely what must be rejected in Shakespeare's comedies.

In As You Like It, for example, the spirited heroine Rosalind — dressed up as a boy named Ganymede — must educate her would-be lover Orlando in the practical realities of marriage, even such a mundane matter as the need for punctuality when one's wife calls. Orlando must learn to stop worshiping a goddess from afar with poetry and come to terms with a down-to-earth woman, with all her physical desires and prosaic demands. Rosalind wants a man who will live with her, not the man of poetic myths who will die for her: "these are all lies; men have died from time to time, and worms have eaten them, but not for love." To make love between man and woman more realistic, Shakespeare recreates it on the model of friendship in his comedies. Orlando and Rosalind/Ganymede get to know each other in a "man-to-man" situation, free of all the artificial conventions of the courtly love tradition (the same happens with Orsino and Viola/Cesario in Twelfth Night). The equality of friends turns out to provide a better basis for marriage than the abasement of the man before his divine mistress in courtly love.

Shakespeare's romantic comedies do not incidentally but essentially culminate in marriage, a moderate but enduring form of love. For Shakespeare, romantic love should be a socializing, not an antisocial force. It integrates young lovers into the larger community, enticing them to renounce their otherworldly yearning for the promise of not heavenly but marital bliss (a lower but more attainable happiness). Like Don Quixote, Shakespeare's comedies make fun of the way that love becomes conflated with religion in the chivalric tradition. Just as the absolute demands of religion must be separated from politics to bring peace to the state, they must be separated from love to achieve the domestic peace of marriage. "Ask for too much, and you'll end up with nothing" is Shakespeare's response to the cult of chivalry.

The parallels between Cervantes and Shakespeare may seem remarkable — even more remarkable perhaps than their dying on the same date — but that is what happened when the two greatest authors of the age confronted the Renaissance's problematic heritage from the Middle Ages and set out to do something about it. Today the world of chivalry looks archaic and quaint to us — and, as a result, harmless. We tend to look back upon it with nostalgia and lament that "the days of chivalry are dead." We may well wonder why Cervantes and Shakespeare devoted so much energy to attacking chivalry. We feel like accusing them of flogging a dead horse. But chivalry is dead largely because Cervantes and Shakespeare flogged it to death. In their day, it was still alive and a powerful force in the real world as well as in literature.

Chivalry did much to shape the late Middle Ages and in many respects shaped that world for the better. But Cervantes and Shakespeare were united in seeing that by the 16th century, chivalry was long past its expiration date. Its false conceptions of love and war were standing in the way of European progress. Whatever civilizing effects the fusion of religion and politics may have had in the Middle Ages, the time had come to separate them — if for no other reason than to end the disastrous religious warfare that began to tear Europe apart in the 16th century and culminated in the horrors of the Thirty Years' War in the 17th.

What we call the European Enlightenment emerged in response to the catastrophic religious warfare that both Cervantes and Shakespeare observed in their day. As we commemorate the 400th anniversary of their deaths, we should be celebrating the way that they helped to usher in the modern world. To be sure, they did not succeed in putting chivalry to rest forever. As a nostalgic ideal, it has been periodically revived over the centuries. In the 19th century, Walter Scott created a new vogue for chivalry with novels such as Ivanhoe. Mark Twain blamed Scott's novels for the American Civil War. In another disastrous case of life imitating art, Twain believed that a generation of would-be Southern gentlemen had hurled themselves into the lost cause of the Confederacy because they were taking as their models the gallant but doomed heroes of Scott's Waverley novels. And Twain wrote A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court in imitation of Don Quixote, once again to expose the delusions and the sham nobility of the Middle Ages.

Thus Cervantes and Shakespeare did not settle the issue of chivalry once and for all. Indeed, in an irony of history, works such as Romeo and Juliet and Don Quixote have been misinterpreted by later generations as endorsing the very romantic idealism Cervantes and Shakespeare set out to undermine. Still, from our vantage point, we can appreciate their achievement. For centuries, chivalric ideals had dominated European literature and even influenced military, political, and amatory behavior in the real world. By the time Cervantes and Shakespeare were finished with chivalry, despite temporary revivals, it never recovered its grip on literature or its influence on the real world. Dying on the same date, Cervantes and Shakespeare could rest content with a literary job well done.