Wagner's Ring Cycle

With Wagner, we reach the peak of Romanticism—he is indeed the arch-Romantic, and the Ring cycle is the culmination of many phases of the Romantic movement. Wagner makes his fellow Romantics look like small-time operators, timid little souls afraid of thinking big. When you just hold a paperback in your hands, the Ring doesn’t look all that different from anything else we’ve read, but this of course is only the bare skeleton of what the work really is. Wagner created on an unprecedented scale. The Ring takes some 15-16 hours to perform—mercifully spread over 4 days, drawing upon all the resources of music, poetry, drama, and spectacle. If nothing else, Wagner’s persistence on the Ring is staggering—he worked on it on and off for 25 years—from 1848 to 1873, with time off to compose Tristan und Isolde and Die Meistersinger. And yet—a tribute to his singlemindedness—the Ring remains one of the most tightly unified works of art—the last few pages of the score clearly hark back to the first. There is then something Romantic just about the conception of the Ring—the idea that such a mammoth work could ever be produced. It finally took a mad king to finance it. The reason Wagner suspended work on it is that it looked like there was no way to get it staged. Wagner’s answer was to get his own stage built to his specifications—the Bayreuth Festspielhaus. The Ring operas make unprecedented demands upon the orchestra and the singers. Wagner had to train them all himself. There are very few singers in the world today who are up to singing the major roles. Wagner refused to believe there were any limits on his art. Blake had all sorts of wild dreams about what he could do if he had a patron. Wagner did not give up until he got his patron. His difference from Blake was his force of will, his egomaniacal personality (see Frye, Fearful Symmetry, p. 412). In addition to artistic talent, he had the shrewdness of a businessman and the soul of a world conqueror. He was the Napoleon of art.

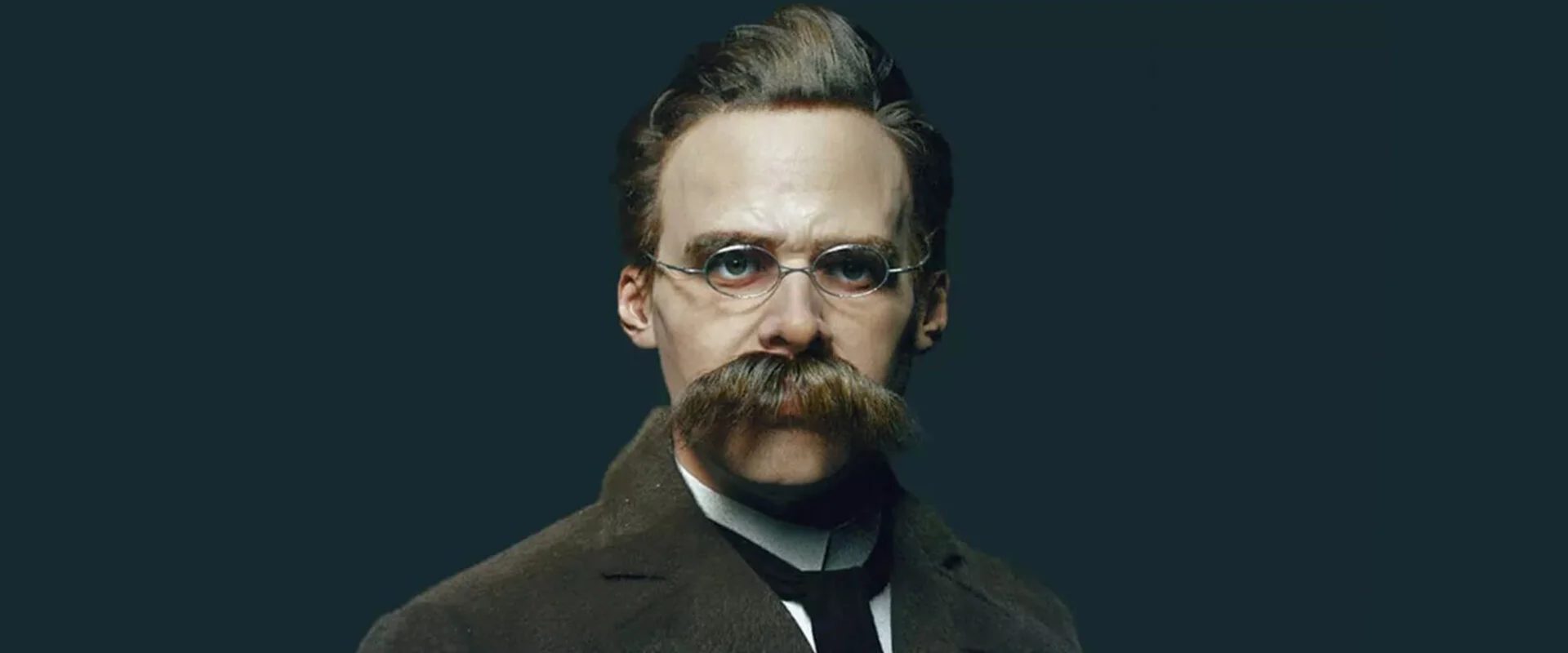

The usual view of Wagner is as a Romantic composer. You can just as well view him as a composing Romantic. His musical talent seems to outshine all his others—it makes us want to consider him in the mainstream of composers. It’s fascinating to see how he develops out of Beethoven and how he leads on to Bruckner, Mahler, Strauss, and Schoenberg. But a good argument could be made—Nietzsche made it—that Wagner’s basic instincts were theatrical, and that he saw music as the most powerful means to achieve theatrical effects. Perhaps he realized that Romanticism was basically operatic in its style—it goes in for grand gestures and rhetorical effects—it’s not an art of understatement. Though he wrote some purely instrumental pieces, he showed little interest in the standard musical forms. His music is organized according to dramatic principles (see Shaw, Wagnerite, p. 2). When he arrives in a particular key, the reason is invariably some dramatic resolution, not some structural musical principle, as in sonata-allegro form. Either as a composer or a dramatist Wagner still ends up a Romantic, but I want to consider him from a third standpoint—I’ll focus on the content of the Ring and take up Wagner as a Romantic visionary in the line of Blake, Percy Shelley, and Byron. Certainly there is no composer whose musical works have more of a message than Wagner’s. This is why Wagner has been the most controversial figure in the history of music—the controversy continues down to this day. No one questions Beethoven’s status today, but Wagner’s is very much in doubt—he finished 2nd in the 1972 Schwann Catalogue survey of “Composers I Like Least”—behind Schoenberg and ahead of Bruckner, two of his musical followers. People sense there is more at stake in Wagner than just music—that he’s a matter of ethical dispute. Hence, for a composer, he arouses unprecedented passions. The combat between Wagnerians and anti-Wagnerians has at times taken on the dimensions of a religious crusade.

This is a good indication that Wagner as an artist knew how to tap the power of myth. To say that Romanticism culminates in Wagner means that in him the Romantic myth-making impulse reached its peak. I singled out Mary Shelley for creating in Frankenstein a myth that has survived to this day, but the fact is it did not survive in the form in which she created it. If it had remained as a novel, far fewer people would know of it today. It took the motion picture to realize the full mythic possibilities of the Frankenstein story—to give it its full popular impact. But Wagner knew how to give life to his myths himself. He didn’t need the cinema because he anticipated most of its effects and basically created what we think of as “movie music.” If he were working today as an artist, it would undoubtedly be in film. In his theater at Bayretuh, Wagner was the first to darken the lights on the audience—in a clear anticipation of film—he wanted his works to have total impact, to absorb the audience’s attention completely. Wagner wanted to create Gesamtkunstwerk—the total work of art. He wanted to bring about a synthesis of the arts—a very Romantic notion, related to the idea of synesthesia. He wanted to draw upon music, words, and scenery—to use as many of the senses as possible to affect the audience. We could see something of this already in Blake. He didn’t just write poetry, he created illuminated manuscripts. The words and the illustrations were intended to work together (See Frye, FS, 186). Blake wanted total control over how his works came out. He handled every aspect from start to finish—he was his own printer and publisher; he didn’t want to be subject to the demands of patrons or editors. The same was true of Wagner—he was his own producer and conductor. If he could have sung all the parts himself, I’m sure he would have (Geck, p. 112, contains an account by the impresario Angelo Neumann of Wagner rehearsing the cast of Lohengrin in Vienna in 1875; evidently Wagner did sing all the parts: “it is altogether impossible to describe the inwardness with which he sang the part of Lohengrin. As for Elsa, he showed her every expression, every arm movement from her very first entry right through her whole long scene with the King. . . . But it was the third act that was the most extraordinary of all, for here Wagner acted and sang almost the entire scene of the bridal chamber.” For Wagner’s total control of his productions, see Sabor, 63: “He combined the offices of stage manager, stage hand, prompter, conductor, singer and actor” and 169: Wagner “let it be known that there was nobody who could possibly stage an authentic Ring after his death”).

In Blake and Wagner, we see the Romantic ego at work in art—everything has to come out of the self—not just a concern for total control—a concern for total impact. In Blake, the visualizations are part of the myth. Blake thought they would help fix his mythic conceptions in the minds of his readers. Blake’s drawings of Urizen make the identification of Urizen and Jehovah more clearly than anything in the text. The kindly old man with the white beard turns out to be a demon. Blake knew that all traditional myths had their impact not just because of sacred texts but because of paintings, statues, temples. He wanted a communal art—a chance to do public murals—he speaks of “national commissions”--Descriptive Catalog (Erdman, p. 531); he makes a suggestion that must have gladdened the hearts of his readers: “I could divide Westminster Hall, or the walls of any other great Building, into compartments and ornament with Frescos” (527). No one jumped at the offer.

Blake knew that myths work below the level of consciousness. Also they have greater impact when they work on more than one person at a time. Wagner understood all this: he thought deeply and wrote extensively about the role of myth in art. He avoided Blake’s mistake—Blake often wrote so obscurely that no one can understand him without volumes of commentary. This tends to dissipate the mythic impact of his works. The amazing achievement of Wagner was to develop a myth very similar to that of the other Romantics, but he did it in such terms that it was much easier for ordinary people to follow it. Wagner was more successful in developing his ideas in Romantic form—everything is presented dramatically in the Ring. Wagner was not as dependent on words—at important points, he lets the music do the talking. Blake worked out a private symbolism. Wagner seized upon the fact that music is supposed to be a universal language. Certainly it cuts across national boundaries better than poetry does. He speaks to people on a more basic level—he speaks directly to their passions, to their will (this was the theory of music advanced by Schopenhauer). It’s more than just the music that gives Wagner’s operas their mythic power. He understood the importance of ceremonies in establishing myths. One of his fundamental insight is that the cult is basic to the myth. It’s no accident that people speak of a Wagner cult. The founding of the theater at Bayreuth was like the founding of a cult. It was the realization of a Romantic dream—to create a temple of art, where the artist would become the focus of the community’s attention. This is true of Bayreuth—while you’re there you’re not supposed to think of anything but Wagner. The artist sets himself up as the center of the world; art takes the place of religion. The artist makes his own community of believers, if not in his myths, at least in him. Wagner lived out the Romantic myth of the creative artist—he suffers for the salvation of his fellow human beings.

One last aspect of Wagner’s use of myth—so far we’ve seen writers making use mainly of Biblical and classical creation accounts. These artists worked within the central tradition of myth in Europe, myths remote in time and space. There is some use of Norse mythology in Blake, but it’s surprising how little use the English Romantics made of their native mythologies. Wagner deliberately worked within the framework of Germanic mythology. At one time he considered writing an opera based on the life of Jesus Christ, but eventually he gave that up for the German story of Parsifal. He wanted to speak to the German people in myths so he went back to the sources of the German people’s myths. This was for him the only viable way to revive myth. This was tied up with the whole Romantic notion of the folk soul—each people has a particular character, revealed in its language and primitive beliefs. This was studied in great depth in 19th century Germany. Its most famous product was Grimm’s Fairy Tales, and collections of folk poetry, such as Des Knaben Wunderhorn. Dealing with Germanic myths gave Wagner greater freedom. There is less of a definite canon than there is with classical myth. There are no definitive versions of the Germanic myths. More important—the artists who had worked with the myths were mostly medieval—the anonymous author of the Nibelungenlied, Gottfried von Strasbourg (Tristan und Isolde), Wolfram von Eschenbach (Parzival). These authors were not as well-known or venerated (Foster, pp. 94-5)—it was not like going up against Homer and Aeschylus, not to mention the Bible or Milton. Wagner could shape the myths freely to fit his own purposes.

Before looking at those purposes, let’s step back and gain some perspective on Wagner. Earlier Romantic creation myths criticize God’s creativity to open up the way for human creativity. Book of Urizen and Prometheus Unbound show the traditional creator god as an evil, restrictive, and incompetent figure. This leads to the notion that man should re-create himself. Man becomes his own creator but then he discovers that he has the same problems as a creator that God did, only he is less able to bear them—living with his loneliness and controlling his own destructive urges. In Frankenstein human creativity appears as something dangerous. Man in his efforts to improve upon God lets loose impulses he should have kept in check. The Romantics begin with a vision of the traditional creator god as impotent, which promises new and unbounded powers to man, but the Romantics become increasingly obsessed with their own artistic impotence, first their lack of power as artists to change the world as they promised, finally even in the failure of their own powers of vision, their own failure to create. In the 2nd half of the 19th century, poets become obsessed with their own inability to write poetry—the withdrawal of the muse, the loss of inspiration. In English we find this theme in Matthew Arnold, G. M. Hopkins, and W. B. Yeats. In German, we find it in Friedrich Hölderlin and Rilke. Wagner embodies the Romantic artist’s ambivalent feelings of impotence and power. For much of his life he was an outcast, banished from the German lands for his role in the Revolution of 1848. So he was himself a failed revolutionary. And yet he persisted in calling for art to have a central role in the building of a new Germany. Finally, through the offices of Ludwig II of Bavaria, it was given to Wagner to realize his wildest artistic dreams as perhaps no other artist ever has.

The two sides of Wagner are reflected in the Ring—that gives it an ambivalence that makes it indispensable to any balanced understanding of Romanticism. The work can be read in the direct line of Romantic theogony. It shows that the current order of the world is the product of a fall, a bad bargain, a dirty deal. This order must be destroyed—burned up—before man can be redeemed, before love can prevail in the world. In particular, one can understand the Ring as following the imaginative pattern of Rousseau’s 2nd Discourse. Man begins in the state of nature, represented by the Rhine maidens at the beginning of Das Rheingold. The fall into civil society, or what Blake calls the fall from innocence to experience, is occasioned by greed and the will to power. The dwarf Alberich seizes the Rheingold and makes it his own—just like the decisive moment in Rousseau’s 2nd Discourse when some man fences off the first plot of land and creates private property or when Blake’s Urizen seals himself off from the Eternals. In Wagner’s Ring, Alberich sets human history in motion. As in Rousseau and Romantic creation myths, this is a story of a Fortunate Fall. The immediate result of Alberich’s action is misery. He enslaves the Nibelungs to work for him. Alberich introduces division into what had been the unified world of nature. He sets the gods against each other. But his fall turns out to be the only way toward progress. It eventually leads to the overthrow of the rule of the gods, and the triumph of the power of love in Siegfried and Brünnhilde. All the suffering must occur so that in the end Brünnhilde can achieve wisdom and recognize the power of love. Ultimately, the fall leads to a higher wisdom.

Read this way, the Ring is obviously a revolutionary work. George Bernard Shaw gave a socialist reading of the work. The scenes of Alberich ruling the Nibelungs show the capitalist entrepreneur exploiting the working class (Shaw, Wagnerite, xvii: “his picture of Niblunghome under the reign of Alberic [sic] is a poetic vision of unregulated industrial capitalism as it was made known in Germany in the middle of the nineteenth century by Engels’ The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844;” see also p. 20) . It may be difficult to sustain this allegory, but undoubtedly socialist ideas were basic to Wagner’s earliest conception of the Ring, and remained in it to the end. But thanks to the complexity of the project, and the number of years he worked on it, Wagner’s understanding of the story deepened as he worked on it. He put more and more of himself into it and that gave a new dimension to the work. We can view it as a mythic projection of the artistic ego, of the Romantic ego. Viewed this way, the tone of the work is much more equivocal. Wagner’s sympathies are more evenly distributed. He focuses on the agony of the god who created the order of this world—that corresponds to the agony of the creative artist. The key lies in the parallels between Wagner himself and Wotan as creators.

To take the work as simply a Romantic manifesto of revolution, Wotan would have to be an unsympathetic figure, since he is the chief representative of the established order. That’s the way our translator sees him: “Poor Wotan! He is only too mortal and fallible, a worried and world-weary one-eyed Wanderer, a sorry philanderer, and a hen-pecked husband, rejoicing only in his huge standing army of heroes” (Robb, Ring, xxvi-xxvii). We’re in a better position to evaluate Wotan because we can compare him to other Romantic portrayals of the gods. Wotan is quite different from the impotent or demonic gods we have seen in the works of the earlier Romantics. He is in many ways the noblest figure in the Ring, and in a very important sense the Ring is most fundamentally the story of his tragedy. Next to him Siegfried inevitably appears immature, and Brünnhilde irresponsible. Though Wotan at times approaches the helplessness of Urizen, he has nothing of the obnoxious self-pity that characterizes Blake’s demiurge. And he is also free of the willful blindness of Percy Shelley’s Jupiter. Wotan recognizes his own destiny—that his doom is coming—he is not caught unawares as Jupiter is. This is ultimately the tragic grandeur of Wotan. He rises to a recognition of what he has done, of how he has been trapped by the very laws he used to rule the world. Urizen and Jupiter were incapable of this realization. Wagner gave a new cast to the Romantic creation myth by treating the central creator god sympathetically—and I think this is in part because he projected much of himself as an artist into Wotan.

Das Rheingold

The opening scene of Das Rheingold offers a proper beginning—the state of nature symbolized by watery depths and darkness. Everything is free flowing—like Eternity in Blake. This is very well conveyed by the music—it begins with what is known as the Nature motif. Wagner’s leitmotif technique was his great musical innovation (although some claim he learned it from Liszt’s symphonic poems). Leitmotifs are themes that recur throughout the work—melodic or harmonic fragments that go to building up the Ring as a whole. They are associated with various elements in the drama—characters, objects, events, and emotions. The leitmotifs are developed symphonically (as in Beethoven), for example, transforming from major to minor key or the notes being inverted. This is the subtlest aspect of Wagner’s art. He can suggest psychological relationships, hidden kinships. He often uses them for dramatic irony. When Hunding notices the resemblance of Siegmund and Sieglinde in Act I of Die Walküre, we hear Wotan’s Spear motif in the orchestra (faintly in the contrabassoon)—that tells us Wotan is their common father. An adequate discussion of the leitmotifs in the Ring would take a few lectures in itself and require musical examples. Listen to Deryck Cooke’s CD Introduction to the Ring. From our standpoint it’s clearly significant that Wagner begins the work with something called the Nature motif. It’s appropriate that the Nature motif is something very simple—an arpeggiated major chord. Wagner takes the 3 notes of the E flat major chord: E flat, G, B flat, and repeats them over and over and over again up and down the scale in the orchestra. This shows how powerful music can be as a representational device for Wagner. Portraying nature by a major chord seems elementary enough, yet it sums up everything Rousseau and Blake had to say about the state of nature. The state of nature in the Ring is one of simple harmony—it’s an obvious musical metaphor. Moreover the state of nature is static. Wagner stays in the same key for an inordinately long time--some 130 measures. Our reaction to the music is the same as Blake’s and Rousseau’s to the state of nature—it’s beautiful but it doesn’t go anywhere. (Geck, 309: “What did Wagner once write about the prelude to Das Rheingold? It had been impossible, he explained, to ‘quit the home key’ of E-flat, because the plot gave him no reason ‘to change it.’”) If the Ring never got beyond the state of nature, it would be boring indeed—15 or 16 hours of E flat major arpeggios—musical minimalism on steroids. In fact the Ring does not stay in the same key. It modulates all over the place.

You can look at the overall musical movement of the work as symbolic of Wagner’s view of the movement of human life. Speaking now in the crudest possible terms: the Ring begins in simple harmony, into which various forms of musical dissonance are introduced—with the dissonance growing as the operas progress—until the work once again resolves into a major chord at the very end, although not the same chord. Götterdämmerung ends on a D flat major chord. Wagner avoids a simple return to the beginning. He does bring back at the end a development of the Nature motif—the motif of the Rhine River—in the concluding orchestral passage, but he ends with something called the Redemption through Love motif. The different key may be necessary to avoid giving the impression that we are simply back to where we started from. A lot has happened in the interim to make that impossible. The musical terms for talking about the Ring are obvious metaphors for the myth it tells. Dissonance must be introduced into the original basic harmony in order to allow progress to take place and to make more meaningful the ultimate resolution back into harmony. This is very much like the pattern of innocence/experience/“organized innocence” in Blake, or Rousseau’s notion that for a few men the state of civil society can be transcended in the direction of back—back toward the state of nature but with the benefit of fully developed human faculties.

For Rousseau and Blake, progress cannot occur in the state of nature or Innocence. It’s too static, cyclical. It’s an undifferentiated unity, with no complexity. To break out of it requires a fall—it makes men miserable, but that forces them to develop. Something very similar happens in the Ring—dissonance is the motive force—it sets the music in motion—but it must eventually be resolved (Donington, p. 60). The main source of dissonance is the motif of the ring itself. Its notes form a chord too, like the Nature motif, but instead of being in the major, its notes, in Deryck Cooke’s words, “make up a complex chromatic dissonance in the minor key, composed of superimposed thirds.” The Ring motif is sounded almost every time the ring is mentioned in the operas, and many times when it isn’t, and thus it gets quite a work-out. Moreover, it gives birth to a whole family of motifs associated with the evil characters—particularly Alberich, Mime, and Hagen. Thus its dissonance progressively undermines the original harmony with which the Ring cycle began. As Cooke says: “this dissonance permeates Götterdämmerung, creating an atmosphere of progressive dissolution. Wagner made the sinister harmony of the Ring Motive eat its way more and more into the fabric of the score, to reflect the fact that the sinister symbol of the ring itself eats its way more and more into the fabric of the drama.” This dissonance makes the final resolution into a clearly established major key all the more powerful—it lasts a full 30 seconds, just building up the D flat major chord.

To sum up: the Ring follows the tripartite structure of Romantic theogony. The basic musical pattern of the Ring is: harmony—dissonance---return to harmony. This corresponds to the stages of the myth. That’s why you cannot explain the movement of the music in Wagner in purely musical terms. It’s not like sonata-allegro form, where you’re required to be in the tonic chord and then modulate into the dominant. As far as Wagner’s musical form is concerned, he could stay in E flat major forever. He had no musical reason for changing keys (Thomas Mann, “Suffering,” p. 320—Wagner follows “not music” but a “literary idea”). Rather he had a dramatic reason—the appearance of Alberich—ultimately a symbolic reason—Wagner is following the mythic pattern.

Returning to the opening scene: the first characters we see in the Ring are the Rhine maidens. They are an excellent symbol for the state of nature. As in Rousseau, humanity begins in a subhuman state—before it develops its specifically human potential. They’re like mermaids—only half-human—the other half fish—living in water. They’re clearly in a state of innocence—they’re very childish—playing around in the water. They don’t appreciate the seriousness of the task they’ve been given—guarding the gold. The state of innocence is fragile, unprotected, liable to fall—that’s what we’ve seen in every myth thus far in this course. The agent of the fall in Wagner is Alberich the dwarf. He is the serpent in Wagner’s Eden. He’s presented as a comic figure at first—he comes seeking the love of the Rhine maidens. All he wants is to lose himself in their charms. Man could be content to live on the level of pure nature and never rise above his instincts, if he could simply satisfy his desires. As in Blake, it’s the force of man’s desires that ends his innocence and sets history in motion. The raging fire burning through Alberich’s limbs is the fire that will eventually ignite the whole world, to be smothered finally by the cooling waters of the Rhine at the end of the Ring Cycle. Watch the fire and water symbolism throughout the work.

Why can’t Alberich’s desires be satisfied?—he’s not made for that, not made for a life of instinct. As he tells the Rhine maidens: “Hard for me—what is easy for you” (Robb, Ring, 6). He has to struggle for what comes naturally to them. That’s man’s problem when confronted with nature’s grace. Strange as it may sound, Alberich is in some ways Wagner’s 1st image of humanity in the work. We have to treat all the characters, not just the humans in the story, as revealing some aspect of the human condition. Wagner’s characters don’t clearly stand, as Blake’s do, for separate faculties or parts of the psyche (the way Urizen, Los, Enitharmon, and Orc do). Wagner’s characters are more rounded; they can stand on their own—that makes the work more dramatic. But still the characters do seem like fragments of an original and larger unity. The Ring Cycle dramatizes that process of fragmentation. At the start of the cycle, the world seems to be well held together under Wotan’s rule. He has the giants working for him—they clearly symbolize brute force. This is like the unfallen state of the Zoas in Blake—reason is in harmony with the passions and instincts. But then we see how precarious is the balance that Wotan maintains. The passions and the instincts fall apart, as in Blake. We then see what this in turn does to the commanding forces in the ego. I don’t want to reduce Wagner’s characters to psychological equivalents as it’s tempting to do with Blake. But I do want to point out that Wagner’s basic myth is not all that different from Blake’s, that he does portray the dissolution of an original psychic whole in the Ring, the emergence of various elements of the psyche at war with each other (for a Jungian analysis of the Ring, see Donington; for the gods in the Ring Cycle representing different powers or faculties, see Cooke, World End, 169: “If Donner, or Thor, is obviously the ‘strong man’ amongst the gods, then Loge, or Loki, is no less obviously the ‘brains’ of the company”).

Looking at Alberich in this first scene: the portrayal of him makes the familiar point of Romantic theogony: man’s creation was defective if he was intended to be happy. Alberich is a dwarf and a hunchback—clearly he was not made to be a lover. He seems condemned to loneliness by whatever god created him. He’s like the Frankenstein monster—the Rhine maidens tell him to go find a sweetheart like himself. There would have been no trouble if Alberich’s searching for love had been accepted—again as in the case of the Frankenstein monster. It is only after his reaching out for sympathy has been rejected that Alberich turns to the will to power, the lust to dominate. The Rhine maidens tease Alberich mercilessly--they encourage his advances, lead him on a wild goose chase, make fun of his deformity. This is an image of nature teasing man with the prospect of a life of instinctive happiness, from which he is forever barred by virtue of how he was made. Nature thus tempts man to conquer it. The Rhine maidens come right out and tell Alberich to come after them—catch us if you can. They’ve shown him he can’t be an integral part of nature—so why not stand above it, become its master, make it serve him, use it for his own power? But nature at first proves to be too slippery for Alberich. He can’t grab ahold of the Rhine maidens. They constantly elude his grasp. Nature is originally formless. No sharp outlines. That’s why it’s pictured in terms of water. It’s hard to take possession of anything in such a fluid state.

In 2nd Discourse and Frankenstein, the world first presents itself to man as an undifferentiated mass of sensations. Man chops up the world into concepts in order to be able to master it. That’s what Blake’s Urizen does: he imposes outlines on the world, horizons. This is also the key to what Alberich does. He gives shape to the formless. After his unsuccessful attempt at possessing the Rhine maidens, the gold makes its appearance. It’s like a dawn and will lead to a kind of awakening. The scene begins in darkness. The gold brings light into the world of the waters. This is a common symbol in folklore and mythology—treasure at the bottom of the waters (Donington, p. 53). Sometimes it is a magic weapon, as in Beowulf. The hero has to make a perilous journey to obtain it—it gives him new power. The treasure reveals itself by its gleam—like fire in the water. According to Carl Jung, this is an archetype for consciousness rising up out of the unconscious. It’s like the Prometheus myth—like stealing fire from the water. This suggests the equivocal value of consciousness for man—it gives him new power but involves new dangers. This fits in with what we’ve seen in Romantic mythology. The myth of creation is a myth of the creation of consciousness, its emergence from the unconscious. In his The Art-Work of the Future, Wagner makes it clear that the emergence of consciousness is at the heart of the myth of the Ring Cycle: “From the moment when man perceived the difference between himself and nature, and so began his own development as man by breaking loose from the unconsciousness of natural animal existence and passing over into conscious life – when he therefore set himself in opposition to nature, and from the feeling of his dependence on her which then arose from that opposition, developed the faculty of thought – from that moment error began, as the first expression of consciousness. But error is the father of knowledge, and the history of the begetting of knowledge on error is the history of the human race, from the myths of the earliest times down to the present day” (quoted in Cooke, World End, 250). This is another way of describing a fortunate fall. Man’s efforts to separate himself from nature are one and the same as the emergence of his consciousness as man. (On this point, see also Foster, 238).

In the Ring, we find a debased version of the folklore motif of finding treasure in the watery depths. It’s not the hero obtaining treasure from the depths, but a churlish dwarf. The treasure will, however, eventually fall into the hands of a hero, namely Siegfried. When the gold appears, the Rhine maidens reveal just how innocent they are. They tell Alberich everything—that whoever makes a ring out of the gold can rule the world. They’re confident because there is a condition attached to forging the ring. One must renounce love to be able to do it—sung to the tune of the Renunciation of Love motif—one of the most powerful motifs in the Ring Cycle. The Rhine maidens think that Alberich is the last person who will renounce love, in view of his demonstrable ardor. But there they miss the point—they think that all things that live embrace love as the highest value, but they’ve just proven to Alberich that love is worthless to him. If he can’t win love, he can if he’s clever win pleasure for himself, pleasure through power, the pleasure of power. We’ve back to Percy Shelley then—what will characterize the world of human experience in the Ring Cycle is a disjunction of love and power. Wagner gives one of the clearest statements of the Romantic myth of creation—the events in the Ring are set in motion by a character who is explicitly willing to renounce love for the sake of power, a detail Wagner introduced to the myth incidentally. Interpreting the action metaphysically: in order to gain power over nature, man must lift himself out of nature. He must deny his being part of nature. Renouncing love means cutting oneself off from the bonds of sympathy that originally united man to nature. Man willfully isolates himself for the sake of power—like Urizen. Love will become possessiveness instead of free interchange. Alberich doesn’t renounce love in a biological sense. It’s not a vow of chastity. In fact he eventually has a son, but he has to bribe a woman with gold to do so. Renouncing love means renouncing man’s place within nature.

This is a dim view of the origin of human history. In Genesis, the human condition is an expression of God’s love, the overflowing of His boundless love. In the Ring, history begins with Alberich’s renouncing of love for the sake of power. But we musn’t forget the basic paradox—Alberich’s power is a kind of impotence. We will see this applies to Wotan, too. Alberich turns to power only because his desires have been frustrated—as in Freudian compensation, power is something negative. And yet in a way little Alberich lives up to the role of hero. He does make a sacrifice. He is willing to give up something precious—love—for the sake of advancing things. Of course it’s just the opposite of a self-sacrifice. In fact it’s the sacrifice of everything else to the self. For a sacrifice of the self we have to wait for the end of the story and Brünnhilde’s dying for Siegfried. [Alberich is like the master in Hegel’s master/slave dialectic—he initiates human self-consciousness and history in his struggle for power, for mastery.] Alberich’s willingness to risk his love life creates self-consciousness. And Alberich is creative. He is an artist. He forges the ring. The ring seems to represent the unformed potentialities that lie dormant in nature. It’s just a lump of gold—malleable but as yet without meaning. It has to be made into an artifact to yield power. This change is reflected in the music. The Rhine maidens’ song of joy in the gold is in a bright, major key melody and harmony. It’s transformed into the sinister Ring motif—in a dark, minor key. Viewing the story in psychological terms: Alberich, like Urizen, sets the ego up above the instincts. In epistemological terms—the conscious mind is set above nature—the power to make concepts. This is why there is something positive in the fall Alberich occasions—it is another case of a Fortunate Fall. It will lead to the development of human faculties. Man was asleep in the state of nature, his faculties dormant. Alberich awakens them. He in effect creates the possibility of being human. Alberich takes us out of our original dependent state, our original absorption into nature.

[In an odd and little-known essay on “Art and Climate,” Wagner writes about man’s need to rise above his passive immersion in the original tropical climate, in which man was too well-provided for and kept in a childish state: “Where nature’s climate, through the all-pervading influence of her most luxuriant abundance, lulls man on her bosom, like a mother her child—there, where we must recognize the birthplace of humanity, -- there, as in the tropics, -- man has indeed remained a child, with all a child’s good and bad qualities. Only when she withdrew this all-conditioning, over-tender influence; where she left man – as a wise mother leaves her growing son – to himself and to his free self-determination; where, due to the waning warmth of nature’s directly fostering climatic influence, man had to fend for himself; -- only there do we see him ripen to the development of fullness of being. Only through the pressure of that need which surrounding nature did not, like an over-solicitous mother, know of and satisfy before it had scarcely arisen, but which he himself had to bestir himself to satisfy, did he become conscious of that need – and also, at the same time, of his power. This consciousness he attained through inner realization of the distinction between himself and nature; and so it was that she, who no longer offered him the satisfaction of his need, but from whom he had to wrest it, became the object of his observation, investigation, and dominion.” Quoted in Cooke, World End, 251. This passage shows how influenced Wagner was by Rousseauian state of nature thinking. It explains Alberich’s allegorical role in the Ring Cycle. He separates man from nature; he creates human self-consciousness by consciously pursuing domination over nature.]

This would be an absurd view of the events if all we were dealing with was Alberich. There’s not much artistic about him. He forges the ring but uses it only to amass treasure. This seems to be a kind of false creativity, the formative impulse misused. [Alberich corresponds to what Blake calls the Spectre of Urthona.]. He’s a shadow of the true artist. To grasp what’s going on, we have to study the links between Alberich and Wotan. The Ring is constantly playing off the heights against the depths. It presents complex parallels between events in Walhall, the home of the gods, and events in Nibelheim, the home of the dwarfs. We see that in the conjunction of the first 2 scenes. Wotan repeats Alberich’s fall; he also ends up renouncing love for power (Foster 92-3; Cooke, World End, 156). We constantly find specific parallels between Wotan and Alberich in the work. For example, in the mighty revenge trio that ends Act II of Götterdämmerung, Gunther and Brünnhilde swear by Wotan, even as Hagen is swearing by Alberich. Late in the Ring Cycle, we learn that, like Alberich, Wotan has also violated nature to gain power. The spear by which Wotan exercises his power is made of wood from the World Ash Tree; the tree has been withering ever since Wotan wounded it. As the Norns sing at the beginning of Götterdämmering: “From the world ash tree Wotan broke away a branch. From this wood the hero shaped the shaft of a spear. The course of time was long. Worse grew the wound in the wood. Leaves fell in their sereness. Then, blight took the tree” (Robb, Ring, 262). (Wotan’s violation of the World Ash Tree raises an interesting issue of chronology in the Ring Cycle. Wotan’s crime occurred before Alberich’s. As the Ring Cycle begins in Das Rheingold, the first thing we witness is Alberich’s violation of nature, but we later learn in Götterdämmerung, as the Norns reminisce about the deep past, that Wotan obtained his spear long before the events with which Das Rheingold opens. After all, Wotan has long been in possession of his spear as scene ii opens, and scene ii immediately follows scene i. As Geck writes: “at the start of Das Rheingold nature appears to be unspoiled only from the standpoint of the Rhine maidens, whereas the truth of the matter is that it was violated long ago, when Wotan hewed a branch from the World Ash Tree in order to make a spear for himself” (Geck, 179; see also Holman, 182). This issue could raise all sorts of questions about the relation of mythic to historical time. But in any case, it shows that Wotan, far from imitating Alberich’s original crime, actually anticipated it.)

Wotan himself draws the overall parallel between him and Alberich during his riddle contest with Mime in Act I, scene ii of Siegfried. When asked to tell who the gods are, he says they’re Lichtalben—“light elves”—and he himself is Licht-Alberich—"Light-Alberich” (Robb, Ring, 176; see Donington, 46, Foster, 153, Cooke, World End, 159-60, Holman, 178); Geck, 220: in a letter, Wagner once “signed himself ‘Your Nibelung prince Alberich’”). Wotan is a mirror image of Alberich; he is in heaven what Alberich is in the depths of the earth. He is the light half of a being of which Alberich is the dark half. In Jung’s terms, Alberich is the shadow of Wotan’s self. Alberich himself points that out to Wotan—Robb, 55—“Would you blame me for the deed you dreamt of yourself?” Alberich tells him that he acted out Wotan’s secret desires; he’s a Doppelgänger for Wotan. Alternatively Wotan is a bright version of Alberich. He has the same motivation (the will to power) but with a nobler cast. This point is made tellingly in the music—another case where one modulation is worth a thousand words. In the orchestral interlude between scenes one and two of Rheingold, the sinister Ring motif gradually is transformed into the noble Valhalla motif—in a major key, sounded majestically in the brass (Geck, 188-89). There’s the point—there is a basic identity behind the power of the ring and the power of Valhalla, but what is sinister in Alberich becomes noble in Wotan. Above all, unlike Alberich, Wotan comes to understand the price he’s paid for power, and ultimately he renounces it of his own free will.

Our first view of Wotan is as a visionary. He awakes from sleep (again—the idea of awakening from sleep) to find that the castle he long dreamed of is now completed. The castle is to be the foundation of Wotan’s rule. From its security he can go out to conquer the world. But in order to get the castle built, Wotan had to make a deal with the giants, Fasolt and Fafner. Here’s an important point about Wotan—he can do virtually nothing himself. He’s the very opposite of an all-powerful creator. Here Wagner could draw upon what is distinctive about Norse mythology; its vision of the gods as doomed and facing overwhelming adversaries (Ragnarok). Cooke (World End, 130) speaks of “a conception peculiar to Scandinavian mythology: the idea that the gods themselves are helpless in the face of elemental forces far more powerful.” Far from being able to create a world out of nothing, Wotan can’t even make a home for himself (in Goethe’s poem “Prometheus,” the rebellious Titan, representing humanity, defies Zeus, telling him that he must leave Prometheus’ home alone; Zeus did not build it and must envy it). Wagner’s Wotan continually has to rely on more elemental forces to do his work for him. To get Valhalla built, he’s dependent on the giants—they stand for brute strength; they can get physical labor done. [Again—as with the master and the slave in Hegel—the slave does the work—he effects changes in the real world according to the master’s wishes—this makes the slave in some sense superior to the master—this idea emerges in this scene]. Wotan doesn’t rule by physical force; he rules by the force of law—the bargains or treaties he’s made; they’re engraved on his spear. Fasolt tells him: “What you are, are you only through treaties” (Robb, Ring, 22). The power of law is the source of Wotan’s strength, but we will see that it’s also the source of his weakness; it binds him (Shaw, 11-12). In Rousseau’s terms, Wotan represents the emergence of civil society out of the state of nature. Man develops laws to control conflicts and secure bargains. In some sense, this marks an advance to a higher order, but, in another sense, the emergence of civil society involves a fall from the peacefulness of the state of nature. For one thing, inequality replaces the equality of the state of nature, in which all human beings are free and independent. Wotan rules the world by his laws and that means he introduces hierarchy. The gods rule over the giants and the dwarfs, while Wotan rules over the other gods. As we soon see, law is not enough for Wotan; he needs the help of the wily half-god Loge; Wotan needs cunning to keep the giants and the dwarfs in line. Wagner’s myth makes it clear—the rule of the gods rests on cheating. Wotan has to employ the trickster Loge to achieve his goals. As in Rousseau, the civil society that emerges out of the state of nature in Das Rheingold has a sinister aspect. As we see over and over again in the Ring Cycle: Property is theft.

Looking at Fasolt and Fafner, we can’t help thinking of Plate 16 of Blake’s Marriage of Heaven and Hell: “The Giants who formed this world into its sensual existence and now seem to live in it in chains, are in truth the causes of its life and the sources of all activity, but the chains are the cunning of weak and tame minds, which have the power to resist energy, according to the proverb, the weak in courage is strong in cunning.” Compared to Blake, Wagner portrays the giants less positively and their restrainers less negatively (though Loge is a demonic figure and his chief characteristic is his cunning ). Wotan and Loge are not lacking in courage, but still there is a basic similarity in the mythic systems of Blake and Wagner (to be clear, Wagner had no knowledge of Blake’s works). Wotan is a Romantic skygod—he dwells in the heights; he’s connected to the conscious powers of the mind. Arrayed against him are all the chthonic forces—the forces of the depths of the mind: giants and dwarfs. These are the passions the skygod must control. We see the same directional symbolism as in other Romantic works. All the threats seem to come from below (Blake’s Orc, Percy Shelley’s Demogorgon), but also salvation must ultimately rise up from below. Wotan knows this. He knows to seek wisdom from the earth—the goddess Erda, the guardian of the Fates, in III.i of Siegfried. It’s as if Percy Shelley’s Jupiter himself made a journey to Demogorgon’s cave in PU (for a comparison of Prometheus Unbound and the Ring Cycle, see Shaw, 64-65). In Blake’s symbolism, a skygod (Urizen) ruling over the giants of the earth represents the triumph of reason over the passions. Wagner’s symbolism of Wotan and the giants is remarkably similar. Like Blake, Wagner reverses the traditional religious symbolism of heights and depths; normally what is above is good (heaven) and what is below is evil (hell). By contrast, just as in Blake’s The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, Das Rheingold concludes with the Rhine maidens singing: “What’s in the deep holds truth and uprightness! False and weak is what rejoices above!” (Robb, Ring, 71).

To return to Wotan’s specific problem in the 2nd scene: to get Valhalla built he had to make a deal with the giants. In return for their labor, they were to be given the goddess Freia, Wotan’s sister-in-law. She is the most beautiful of the goddesses—the Norse Aphrodite. Most of the love motifs in the Ring grow out of Freia’s motif. As we soon learn, she tends the golden apples that give the gods eternal youth—love gives vitality to the world (Cooke, World End, 192). Thus in offering Freia in exchange for getting Valhalla built, Wotan is in effect renouncing love for power. In his urge to see his vision made real, Wotan becomes blind to any human considerations. Essentially, what he says to his wife Fricka is: “Freia—don’t worry about her—we’ll cross that rainbow bridge when we get to it.” Wotan is like an artist—he will sacrifice anything for the sake of his vision, including all human relationships. This is what we saw in Frankenstein—the creator in man is willing to let the creature suffer. The desire to create can stifle all sympathetic impulses. This is the reason why achieving power requires renouncing love. We see this most directly in the fact that Wotan’s rush to get Valhalla built has led to trouble with his wife. When we first see him, he’s arguing with Fricka, but, then again, he’s always arguing with Fricka. He says she wanted the hall built as much as he did, but the reason was that she wanted to be able to keep an eye on him. It’s not for nothing that Wotan is called the Wanderer in Siegfried—he’s continually straying from the straight and narrow path and as a result several of the main characters in the Ring are Wotan’s children, and none of them by Fricka. She viewed Valhalla as a way of possessing Wotan—keeping him for herself. You might say that Fricka’s possessiveness is the origin of all the trouble in the Ring. Wotan tells her: “If you would keep me confined in my fastness, you yet must grant to my godhood that, in the castle’s confines, still I may conquer the world that’s without. Wandering and change are loved by all.” (Robb, Ring, 19) Because Wotan feels tied down to a woman he doesn’t love, he turns to the desire to rule the world. As with Alberich, frustration in love leads to will to power. Knowledge of Wagner’s own life suggests that in the scenes between Wotan and Fricka, Wagner, much like Blake, has lifted the personal up to the level of the mythic. Wagner had an unhappy marriage and many love affairs. He was always searching for the perfect woman who would give herself to him completely, no questions asked. This situation is reflected in many of the heroines in his operas, including Senta in The Flying Dutchman and Elsa in Lohengrin.

Returning to Wotan’s story—he gets more and more deeply enmeshed in a web of fate. He needed the giants to build Valhalla and then he needs Loge to get him out of the bargain with the giants. Loge tells him he has to turn now to the Nibelungs. Wotan is asking the giants to renounce love—to accept something in place of Freia. Loge has searched the whole world and found only one being who didn’t regard love as the most valuable thing in the world. That of course was our old friend Alberich, who opted for the ring instead of love. The giants, Fafner particularly, seem amenable to the idea of ruling the world rather than possessing Freia. So Loge and Wotan set off to Nibelheim to try to win the ring from Alberich. There they find that the fall Alberich set in motion is progressing. The Ring Cycle consists of a series of falls. The Nibelungs used to be in the Walt Disney tradition of dwarfs, whistling while they worked: “Once, in our carefree, smithing days we made gear for our women, winsomely forged, delicate Nibelung toys. We laughed with joy as we toiled” (Robb, Ring, 40-41). But now they are toiling away in Alberich’s sweat shop.

With Alberich and Mime, we have another master-slave relationship in the Ring. Mime hopes to switch positions with Alberich: “I, who had once been the bondsman, as freeman thence should command” (Robb, Ring, 41). [See also Siegfried, I.iii, where Mime says: “Alberich, you whom once I served, shall in your turn be servant to me” (Robb, Ring, 195)]. As in Rousseau, once property is established and hence inequality, we enter the world of class struggle for power and pre-eminence. This is the most “Marxist” scene in the Ring Cycle. And it corresponds to the fall into civil society in Rousseau’s 2nd Discourse. This moment in Rousseau’s account of humanity’s fall out of the state of nature is the imaginative core of Wagner’s Nibelung myth: “The first person who, having fenced off a plot of ground, took it into his head to say this is mine and found people simple enough to believe him was the true founder of civil society. What crimes, wars, murders, what miseries and horrors would the human race have been spared by someone who, uprooting the stakes or filling in the ditch, had shouted to his fellow-men: Beware of listening to this impostor; you are lost if you forget that the fruits belong to all and the earth to no one!” (Rousseau, 141-2). Alberich is like the mythical man in Rousseau who created private property. He appropriated the Rhine gold for himself. He is now amassing more and more property by exploiting the labor of his fellow men.

It’s the same kind of fall we saw in Rousseau and Blake. To leave the state of nature for civil society, or to leave Innocence for Experience, is to lose the initial harmony with nature and be plunged into misery. But this still is a kind of progress, an advance in human creativity, seen for example in Alberich’s ability to create the Tarnhelm. Alberich has set a plot in motion that will eventually lead, no thanks to him, to the redemption of humanity. Alberich’s story is an excellent example of a principle that dominated the dialectical thinking of the 19th century from Hegel to Marx to Nietzsche. You might call this principle the positivity of the negative. What at first looks like a loss or a fall turns out to be progress in the long run and the only path to development. That’s how a negative becomes a positive. As Daniel Foster sums up the progression of the Ring cycle myth: “Throughout this opera Wagner presents us with an epic theogony for the whole world of the Ring. Symbolic of human cultural evolution, Das Rheingold portrays Wotan and his gods’ extrication from nature and their installation in Valhalla. Beginning with a portrayal of nature and nature gods through the Rhine, his daughters, and the as yet unformed lump of Rhinegold, Wagner progresses to the disruption and corruption of nature through the theft of the Rhinegold, the building of Valhalla, the crafting of the ring and the Tarnhelm, the unnatural slaying of brother by brother, and the final supplanting of nature by culture as the gods enter their new abode. . . . Valhalla, the cultural seat of a newer, more civilized regime, has replaced the primordial and unformed world of the Rhine and an artificial light source now shines in place of the sun as culture thus evolves out of nature” (Foster, 90).

Returning to the story back in Valhalla: Wotan and Loge are successful in winning the ring from Alberich, except for one problem. Alberich gets to put a curse on the ring, which dooms everyone to death who possesses the ring, and dooms everyone to covet it who does not possess it. The ring becomes something like a perpetually forbidden fruit. You can view Alberich’s curse as the curse of consciousness. Once man lifts himself above the state of nature, he’s doomed to misery. For one thing, his awareness of his mortal destiny can poison all his life. But once you know what consciousness is, you won’t willingly forego it. This is particularly true of Wotan. He’s wracked by his awareness of impending doom, yet he is driven to learn more and more about his fate. This shows why the Fall is irreversible and indeed Alberich’s curse maintains its force throughout the Ring. It becomes an important musical motif, which Wagner uses with great irony. For example, in Act I of Götterdämmerung, Hagen welcomes Siegfried to Gunther’s court to the tune of the Curse motif, foreshadowing the tragic outcome of this visit (Sabor, 140). The curse puts Wotan in an impossible situation. He himself covets the ring, but he knows if he tries to possess it, he is doomed. If he didn’t know that, he surely does after the earth-goddess Erda appears to warn him away from the ring. Right after that he gets further confirmation, as the curse claims its first victim. Fafner kills Fasolt in a fight over the ring. So Wotan cannot afford to take possession of the ring. But he can’t afford to let the ring go either. Fafner doesn’t seem to want to do much with it. In fact, we later learn that he turns into a dragon to be able to guard the ring better. All he wants to do is sit on the ring. This seems like the reductio ad absurdum of possessiveness. Fafner allows himself to be distorted beyond recognition for the sake of guarding the ring—a symbol of how greed can transform a man. (In Shaw’s allegorical reading of Fafner: “The world is overstocked with persons who sacrifice all their affections, and madly trample and batter down their fellows to obtain riches of which, when they get them, they are unable to make the smallest use, and to which they become the most miserable slaves”—22). But the real problem is not Fafner but Alberich. He wants the ring back and, if Wotan doesn’t want the world to fall into the dwarf’s hands, he must find a way to neutralize the power of the ring. His plan unfolds in the next opera, Die Walküre. That Wotan is already thinking of a plan is shown by the mysterious appearance of the Siegmund’s Sword (Nothung) motif in the orchestra as Das Rheingold ends.

Die Walküre

Die Walküre opens with our first glimpse of the human world in the Ring Cycle. Indeed, the entire first act takes place among mortals. As in Frankenstein, where the irony is that the monster is more human than his creator, in the Ring the mortals can be more godlike than the gods. In fact, Wotan’s impotence as a god is finally shown in the fact that he must sire humans to rescue him, to perform the deed that he cannot (regain the ring). The humans in the Ring—at least the best of them—are better than the gods, because they’re potentially free of the curse of the ring and thus capable of love in a way Wotan is not. Only humans in the Ring can experience true love: Siegmund and Sieglinde, Siegfried and Brünnhilde (she must lose her divine status and become mortal to experience true love; Holman, 217). Wotan’s plan is to rely on the greater freedom of the mortals. He sires a race—the Wälsungs—from whom he hopes to get a hero who can free him from Alberich’s curse, a hero who can save him. You can see the momentous reversal here—the god has to turn to a man for his salvation in the Ring. We have seen all along in Romantic creation myths that they transfer the power of salvation from God to man. In Act I of Die Walküre we meet Wotan’s first candidate for the hero—Siegmund. With its sustained lyrical passages, this is in many ways the most beautiful part of the Ring musically. The claims of love begin to reassert themselves in the world of the Ring. The love motifs express yearning, reaching upwards; they encounter efforts to restrain passion—particularly symbolized by Wotan’s Spear motif—a stern, descending minor key scale. We have a kind of battle of the motifs in Die Walküre. Love has to struggle to survive—the order of the gods has come to be reflected in the world of men. Love is used by power-hungry men for their own ends. Siegmund is fleeing a battle in which he tried to defend a girl who was being forced into a marriage against her will. And of course the love that Siegmund finds in Act I encounters even more opposition. He falls in love with Sieglinde, who turns out to be his sister—the most unconventional love possible—it goes against the rules of morality. We see again the revolutionary potential of brother-sister incest, which we first encountered in Blake’s America and returned to in Byron’s Cain. This love arouses the wrath of Sieglinde’s husband, Hunding, whom Sieglinde was forced to marry. As Act I ends, Siegmund and Sieglinde have discovered they are brother and sister and proclaim their love for each other in rapturous terms. Siegmund will have to fight Hunding for her on the following morning.

Act II of the opera is the core of the Ring. It contains the most important confession from Wotan and yields the deepest insights into his character. As Act II opens, Wotan is summoning his daughter, the Valkyrie Brünnhilde, to aid Siegmund in his fight against Hunding. But unfortunately Fricka shows up to speak up for Hunding. She is the goddess of wedlock, and must champion a husband’s rights. Moreover, nothing could be more offensive to the gods than this incestuous pair, Siegmund and Sieglinde. Wotan begins speaking in favor of love, defending their passion as holy in itself. He also speaks as a revolutionary against Fricka’s conservatism. She says very primly: “When was it ever seen that brother and sister physically loved each other?” Wotan answers: “You’ve seen it today.” This is an important indication of the character of Wotan. He’s a visionary ahead of his time—like an artist. Fricka keeps telling him that he’s broken all his vows, above all, his wedding vows to her, and thus made a mockery of the honor of the gods. Wotan answers Fricka the way an avant-garde genius would speak to a reactionary art critic—the way Wagner would speak to Eduard Hanslick, or the way Walther von Stolzing speaks to Beckmesser in Die Meistersinger. Wotan says to Fricka: “you’ve never learned—though I would teach you—the things you can’t comprehend, for first they have to take place. All you know is what is customary, whereas my thoughts foresee the events yet to come” (Robb, Ring, 101-2). Fricka is bound by the rules of the past; Wotan can see, and will, the future. You see here how different Wotan is from the usual demiurge of Romantic myth. He’s something of a revolutionary himself—like a misunderstood artistic genius.He does not stand up for the established order. Instead he wills the future when it will be destroyed.

And there’s something of this in his son Siegmund, too: “Whatever I thought right others looked on as wrong. What looked like evil to me others favored as right!” (Robb, Ring, 82; Mann, “Suffering and Greatness,” 340, Donington, 130). Wotan has bred Siegmund to be this way. Siegmund is an outlaw; he fights the established ways. He must be free of all conventional restraints to be able to perform the daring deed that will free the gods. But Fricka seizes upon this point—the fact that Wotan has deliberately raised Siegmund to be unconventional and autonomous. She relentlessly strips Wotan of all his hopes for his hero—above all, his illusion that Siegmund is free, independent of Wotan, and thus clear of the curse of the ring. An intense scene unfolds as Fricka chops away at Wotan’s every defense, culminating in the moment when Wotan claims of Siegmund’s sword: “Siegmund achieved it himself in his need.” Fricka answers: “you shaped both his need and the sword of his need” (Robb, Ring, 103). Fricka cleverly traps Wotan. Siegmund is his creation—he raised him to be what he is. He created Siegmund’s need. By not providing for him, by not giving him an easy life, Wotan steered him in a certain direction, attempting to develop his independence and self-reliance.

As in Rousseau and Romantic theogony, lack of providence is the only true providence—the gods’ failure to provide for man forces him to create himself. But that still makes Siegmund an extension of Wotan. Wotan planned for Siegmund to turn out the way he did. Siegmund is only a projection of Wotan’s will to power. That explains one of the strangest uses of a leitmotif in the opera, something that has puzzled many analysts. When Siegmund pulls the sword out of the tree in Act I (Robb, Ring, 94), he proclaims his “holy” love for Sieglinde, but he sings it to the Renunciation of Love motif. This seems peculiar, but now we can see the logic. Siegmund thinks that by seizing the sword, he’s serving his own love, but he’s actually acting out Wotan’s plan, serving the god’s power schemes. Wotan provided the sword, but to slay Fafner, not Hunding (Cooke, World End, 3-4). Here is another case of a motif used for dramatic irony. Wotan’s plan collapses as Fricka disproves Siegmund’s independence. Wotan tries to wriggle out of the trap Fricka springs on him, but she knows all his tricks and all his equivocations. Finally he has to make Brünnhilde also take an oath not to aid Siegmund. Notice how strange all this is. One would expect the god to support law and order, but Wotan has to be forced to do so against his will. He is truly trapped in a web of fate. He has to uphold the holy honor of his eternal wife. Wagner places Wotan in a genuinely tragic dilemma—he is caught between the law of the present and the new values of the future. (This is the tragic situation par excellence according to Hegel—like the conflict in the Oresteia, or that between Creon & Antigone [see Cooke, World End, 33], or that between Athens & Socrates.) Wagner gives a balanced presentation. Fricka, even if she is based on Wagner’s wife, is by no means a caricature. Wagner gives her a musically beautiful and noble statement of her case.

Wotan is now tormented in his frustration: “The chains I welded now hold me fast—least free of all beings” (Robb, Ring, 106). This leads to the center of Act II—what is usually known as Wotan’s monologue. The first thing to notice about Wotan’s monologue is that it’s not a monologue but a dialogue (Cooke, World End, 330). Wotan is talking to Brünnhilde. But this is like talking to himself, for, as she says, she is only an extension of his will. That’s the whole problem, as we will see. Whenever Wotan talks, he’s talking to himself—wherever he looks, he sees only extensions of his will. He begins the monologue with the idea that he turned to power only after he was too old for love. He recalls how he has fallen into his dilemma: “I who by treaties was lord, by these treaties now am a slave” (110). He is bound by his own laws. As in Rousseau’s 2nd Discourse, the emergence of civil society leaves people entangled in a web of laws that restrict their freedom. Thus Wotan needs a paradox, what he calls the “friendliest foe”: “Now could I create one who not through me, but through himself would express my will?” (111). He thought that this would be Siegmund, but Fricka found out the fraud. We hear the ultimate despair of the creator god: “I feel disgust just seeing myself in all the deeds I accomplish! The other, that I have longed for, the other I never see. The free are their only creators—slaves are all I can make!” (111). Wotan’s creations are necessarily inferior to him; he has to be worshiped by beings he considers beneath him. [As with the master in Hegel—the men who recognize and thereby validate his worth are not his equals; therefore his glory is hollow and unsatisfying]. This makes his rule feel worthless and empty. Wotan is searching for the Other but all he sees is himself in everything he creates. Here is the despair of the Romantic ego; it wants to be able to create the whole world out of itself, but then finds itself to its horror all alone in that world.

Consider this on the model of an artist’s relation to his characters. Wotan is to the Wälsungs as Wagner is to all the characters in the Ring. They are Wagner’s creations. The question is: are they free to do what he is unable to do? In one view of artistic creation, it’s compensation. The artist acts out his dreams in his art. Wagner clearly put a lot of himself into the characters of the Ring. He identified with them. He named his son “Siegfried.” Wagner had the same problem as Wotan—he couldn’t find the Other. He wanted to dominate everyone around him—he ended up surrounded by yesmen, people who blindly followed his will, bowing to his genius. What were they worth to him? They were like slaves, and indeed he wanted to be addressed as “master.” The only truly independent being in his circle was Nietzsche, but when Nietzsche raised questions about Wagner, it led to a break in their friendship. Wagner was forced to destroy all his ties to other human beings because of his titanic ego. This is just what happens to Wotan. That’s the curse of the ring: “What I love I now must surrender, murder what I’ve most cherished” (112). Wotan must destroy everything he loves—needless to say, these words are sung with the Renunciation of Love motif in the background.

This is just what we saw in Frankenstein: the Romantic egotist is impelled to murder the thing he loves. Unlike Frankenstein, Wotan recognizes what he’s doing—therefore he wills his own destruction. We reach a turning point in Act II—a god who wishes the overthrow of his own dynasty. In the emotional, rhetorical, and musical climax of Wotan’s monologue, he invokes fate upon himself: “So take my blessing, Nibelungen son! What deeply disgusts me is yours to inherit; my godhead’s empty display; so gnaw away, glutting your greed” (Robb, Ring, 113). It is as if Blake’s Urizen or Percy Shelley’s Jupiter came to recognize his own emptiness and yielded to his rebellious adversary, Orc or Demogorgon. Unlike most tyrants, Wagner’s Wotan does not need to be defeated in battle to realize the error of his ways. The figure who should be the evil demiurge in Wagner’s myth shows his nobility in his awareness of his own wrongdoing.

But this recognition has not yet sunk deeply into Wotan’s soul—it remains only on the surface. His pride is still too strong, as witness the way he treats Brünnhilde. He wants to encounter someone independent of his will, but the moment he finds such a person, he turns on her. One word of contradiction from Brünnhilde and he flies into a rage. “Who are you, if not the blind and tame tool of my will?” (114). He wants blind obedience from the Valkyrie—this resembles the scene between Frankenstein and the monster in the Alps (another scene of the creature confronting the creator). And like the monster, Brünnhilde will prove that she is an extension of Wotan’s will in a deeper sense than he can understand. She will act out his secret desires—she will act out what is noblest in him—his self-destructive urges. She will truly be the friendliest foe. By disobeying Wotan, she will obey him in a deeper sense. At first she tries to carry out Wotan’s conscious will—she goes to announce Siegmund’s death to him in the Todesverkündigung scene: it is very solemn and moving, dominated by the newly introduced Fate motif. Brünnhilde tries to present the matter as delicately and attractively as possible to Siegmund—he’ll be going to Valhalla to join the other heroes and meet his father. But when he learns that Sieglinde cannot accompany him, he refuses to go. The human is nobler than the god—Siegmund will not sacrifice love for glory. This is an important reversal of the pattern we’ve been seeing—we finally see someone who makes a decision in favor of love (Cooke, World End, 336-37). This deeply affects Brünnhilde. She is carried away with the power of Siegmund’s love for Sieglinde and decides to disobey Wotan and to stand by Siegmund in battle. A god learns a lesson in nobility from a mortal. But in the event, her help doesn’t count for much. At the decisive moment, Wotan appears and uses his spear to shatter Siegmund’s sword. What a god creates he can destroy. Furious about what Brünnhilde has done, Wotan as Act II ends swears vengeance against her.

Act III is devoted to the confrontation between Wotan and Brünnhilde. He vows to strip her of Valkyrie status, put her to sleep, and leave her to the 1st man who comes along. Brünnhilde pleads her case. She yielded to the power of love: she tells Wotan that in standing up for Siegmund all she did was “to love that which you have loved” (149). This only embitters Wotan further. But then Brünnhilde reveals the big news. Sieglinde bears the most glorious hero in her womb: Siegfried. Earlier in Act III, she had already told Sieglinde of her pregnancy and she reacts by singing the Redemption through Love motif—its one appearance in the Ring before the very end. This shows the great promise of Siegfried. Wotan doesn’t understand it yet, but Brünnhilde has worked to carry out his plan. Siegfried will turn out to be the hero he is seeking. Nothing works out according to the god’s conscious design in the Ring. Whatever Wotan plans, goes awry. Whenever he thinks things are going in the wrong direction, then they’re working out right. He’s moved by Brünnhilde’s pleas and agrees to surround her with a magic fire while she’s sleeping so that not just any man can wake her up, but only a great hero. Wotan realizes that it will be someone freer than he, the god. He doesn’t realize what the vocal line is telling us—he sings the Siegfried motif.

The opera ends with a long lyrical passage, known as Wotan’s Farewell. This is a moment even a more painful for him than ordering the death of Siegmund. He loves Brünnhilde as no one else, as his one true soul partner, as an alter ego. This is what she herself tells him: “Must you sever what once was as one, abandon half of what is your being?” (149). We can trace how Wotan progressively cuts himself off from love. At first, he’s willing to risk losing the goddess of love, Freia. Then he must sentence his son Siegmund to death. Finally he must sever himself from part of his soul—his wishmaiden—what would be called his anima in Jungian psychology—all the tender, feminine aspects of his soul that made him capable of love. [In Blake’s terms, Brünnhilde would be Wotan’s Emanation—what Ahania is to Urizen—his wisdom. Here’s an interesting parallel: in Book of Urizen, Blake has Los surround his Emanation Enitharmon with the fires of Prophecy, a form of possessiveness (Frye, 374)]. Wotan never recovers from this parting with Brünnhilde. He has killed something in himself and can never take joy in life again. As he puts her to sleep, we hear again the Renunciation of Love motif in the orchestra. Brünnhilde loses her godhood and yet this turns out to be a blessing in disguise. As she herself says much later in Act I, scene ii of Götterdämmerung to her sister Waltraute: “So my punishment turned to a blessing” (286). Her loss leads to a new freedom for her. (It is another fortunate fall.) She will be free of the curse of the ring, free to love in a way that Wotan is not. For the moment, she is returned to the state of nature, which as always is closely related to sleep. She becomes dormant—her potentiality is suspended. The motif of the Sleeping Brünnhilde is, as Cooke argues, related to the original Nature motif—a rhythmic variant of the rising and falling pentatonic theme of the Rhine maidens—it is also related to the song of the forest bird in Siegfried (all forms of nature). As Die Walküre ends, Wotan promises that a man who fears his spear will never step through the fire that surrounds Brünnhilde. He sings this to the Siegfried motif. Siegfried is the answer to Wotan’s need—a hero truly independent of him, which takes us to the next opera.

Siegfried

Siegfried marks a new beginning. A return to the state of nature and another fall from it. A whole opera devoted to the education and growing up of a hero—eine Heldensbildungsoper (Foster 163). Siegfried fits the archetypal pattern of the hero, as studied by authors like Otto Rank, Carl Jung, and Joseph Campbell. Like the archetypal hero, Siegfried is conceived and born in hectic circumstances. His parentage is unclear as far as he knows, he’s raised by a foster parent, he’s threatened with death in his youth, he has to slay a dragon, he acquires a magic helper (the forest bird), he rescues a maiden from imprisonment by fire. Siegfried would make a fascinating study for anyone interested in the hero-archetype. Wagner seems to have had an intuitive grasp of the covert psychological meaning of the various hero myths. You come to very peculiar conclusions when you reflect on the implications of Wagner’s version of the myth. Shades of Oedpius: In order for Siegfried to emerge into manhood, he has to murder the man he’s been told is his father (Mime) and marry the woman he at first mistakes for his mother (Brünnhilde). (Donington, 189-96; Mann, “Suffering and Greatness” 312; Holman 226). We can have a Freudian field-day with the work, especially once supplied with the fact that Wagner’s own parentage was quite uncertain, and that he was raised by a stepfather who may very well have been his real father. It’s not our business to pry into Wagner’s psychic life. Still the psychological implications of the hero archetype are important for our purposes.

The hero’s story represents psychic growth toward independence, the freeing of the individual from domination by his parents—to live his own life. What’s important for Wagner’s myth—Siegfried must be free of all authority to meet the need of the gods. His story keeps coming back to his learning how to come to terms with his mother and father archetypes, particularly in his dealing with the dragon. I have always been skeptical of archetypal criticism that associates dragons in myth with the mother archetype. What have mothers got to do with dragons? Then Wagner showed me the connection. As Siegfried approaches the sleeping Fafner in Act II, scene ii to slay the dragon, we hear the beautiful passage known as the Forest Murmurs. Thinking ahead to his encounter with Fafner, Siegfried thinks back to the mother he never knew: “Ah, might the son only see his mother! Lovely—mother, who lived on earth!” (Robb, Ring, 210). On some level, Siegfried associates the sleeping dragon with the sleeping Brünnhilde, whom he soon mistakes for his mother. To win Brünnhilde, Siegfried will have to overcome his attachment to his mother, symbolized by the dragon threatening to devour him.

As Wagner portrays Siegfried, he is a child of nature (Foster, 121). He feels kinship with animals, and loves playing with them. And yet he senses he is not one of them; he senses he has some kind of higher calling, which is tied to the secret of his parentage. That’s what prevents him from just running away from Mime—he wants to learn the secret. As he tells Mime: “For I like the beasts more dearly than you: trees and birds, and the fish in the brook. . . What is it then that makes me come back? If you’re wise then tell me this” (Robb, Ring, 164). Siegfried [a masculine version of Blake’s Thel] wants to grow up, get out in the world, make a name for himself. Wotan has had nothing to do with raising him. Instead the task has fallen to Alberich’s brother Mime. Mime has been both father and mother to Siegfried—a grotesque parody of a family situation. (“I am your father and mother combined,” says Mime, Robb, Ring, 166). The scenes between Mime and Siegfried are often very comic—indeed this opera has much more comedy than the others. Still, when you think about it, it provides a frightening image of family life, especially in the scene of Mime trying to instill his little catechism of gratitude into Siegfried. This is the only portrayal of raising a child in the whole Ring cycle—and no love is involved, only will to power. Mime wants to use Siegfried the way Wotan wanted to use Siegmund and the way Alberich will want to use Hagen in Götterdämmerung to win the ring for him. In each case the “offspring” does not live up to the father’s expectation; he has a will of his own. Siegfried is the uncorrupt man in the state of nature or the state of innocence—he doesn’t know what fear is. (In Shaw’s allegory (p.. 57), Siegfried is “a type of healthy man raised to perfect confidence in his own impulses by an intense and joyous vitality which is above fear, sickliness of conscience, malice, and the makeshifts and moral crutches of law and order which accompany them. Such a character appears extraordinarily fascinating and exhilarating to our guilty and conscience-ridden generations, however little they may understand him”). In the rest of the Ring Cycle, we will watch various worldly and experienced figures trying to corrupt Siegfried: Mime, Alberich, Wotan, and Hagen all try to use Siegfried in their schemes for power (Donington, 175).